Side Menu:

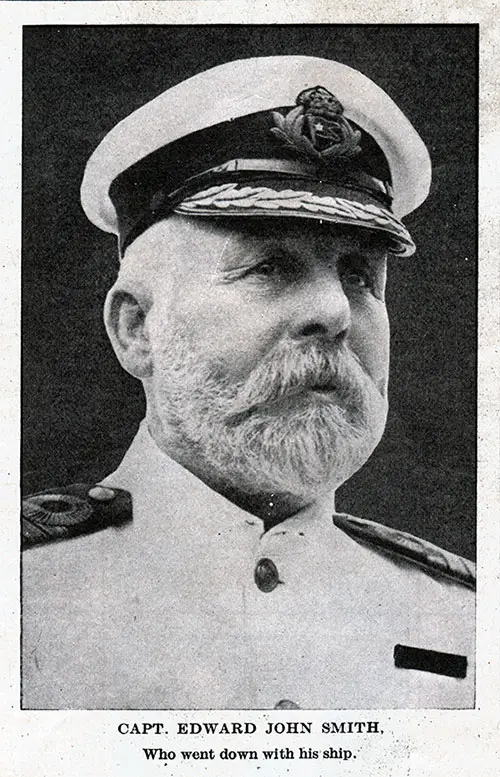

Captain E.J. Smith - R.M.S. 'Olympic' and Two Collisions

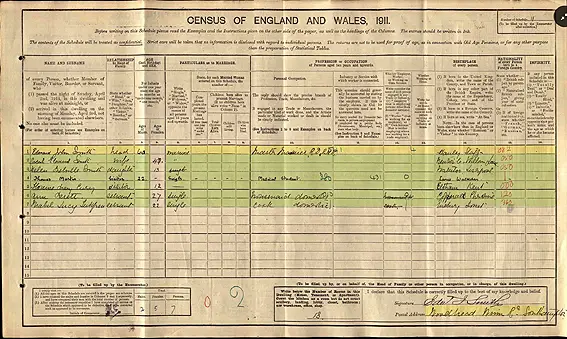

The 1911 Census gives a fascinating insight into the Smith household at this time - a house with 18 rooms and two servants. (Click to enlarge)

Thanks to the 1911 census of England and Wales, we have a glimpse into the Smith household living at Woodhead in Southampton. The house is listed as having 18 rooms and accommodating seven people - 60 year old Edward John Smith (who signed the document), his 47 year old wife Sarah Eleanor Smith (he age is heavily corrected - did EJ struggle with her age?), their 13 year old daughter Helen Melville Smith (with the word "single" crossed out) and two servants - a 27 year old domestic housemaid named Ann Brett, and a 22 year old domestic cook named Mabel Lucy Lulpeu (spelling unverified). At the time of the census there were two visitors to the Smith residence - 22 year old Thomas Martin and 12 year old Lorence May Curry.

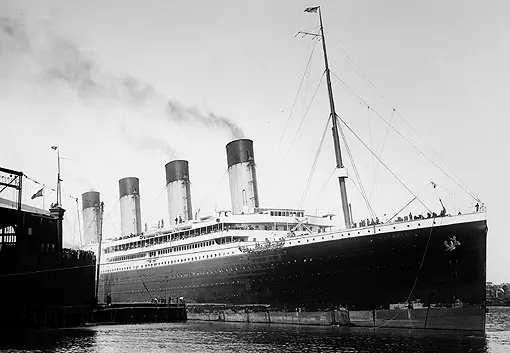

RMS Olympic arriving to the NY harbour on her maiden voyage, June 21, 1911 with Captain Smith visible on the bridge (Click to enlarge)

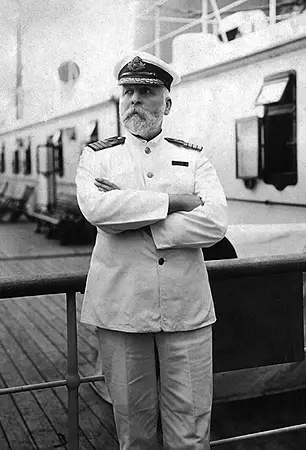

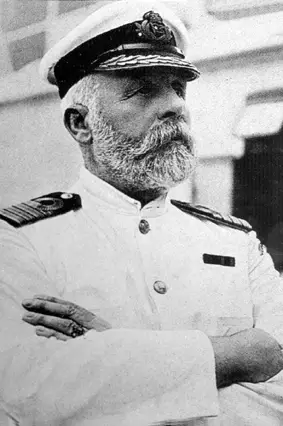

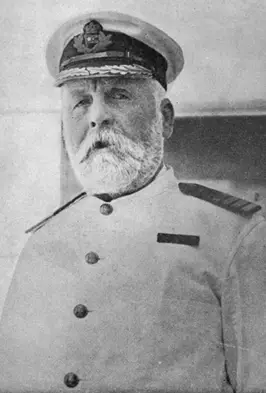

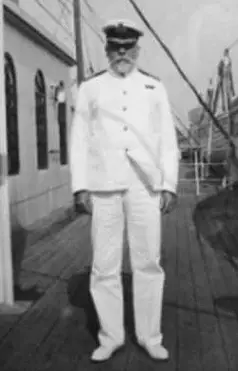

Captain Smith poses on the starboard side

of the officer's quarters aboard RMS Olympic

in 1911. (Click to enlarge)

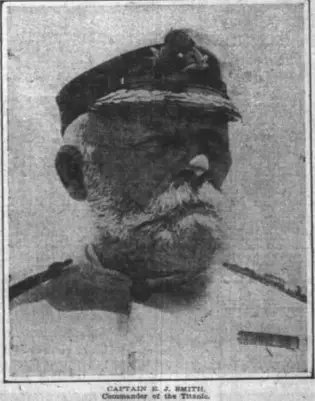

The White Star Line launched a new class of ship - known as the Olympic class - and as one of the most experienced sea captains Smith, now holding the rank of commander, was called upon to take command of the maiden voyage of RMS Olympic from Southampton to New York in June 1911. His White Star records officially list him as Commander from the 15th of May, 1911.

At 45,324 gross register tons, 882ft 9 inches in length and 9 decks tall, the largest ship in the world, attracted great attention, with the White Star Line timing the start of her first voyage to coincide with the launch of her sister ship Titanic.

But as the ship was docking at Pier 59 in New York harbour on the 21st of June 1911, one of twelve tugs assisting was caught in the backwash of the Olympic, spun around and collided with the larger ship and was momentarily trapped. Blame was later apportioned entirely to the tug in subsequent court hearings, not to mention that the Olympic was under a harbour pilot at the time.

In the San Francisco Call of 29 August 1911 (courtesy Gary Cooper) Captain Smith when asked about the Olympic's coal consumption on her maiden voyage answers "that is a coal story I am not priviledged to speak about" and then goes on to tell a light humoured story involving a sea burial and coal. (Click to enlarge)

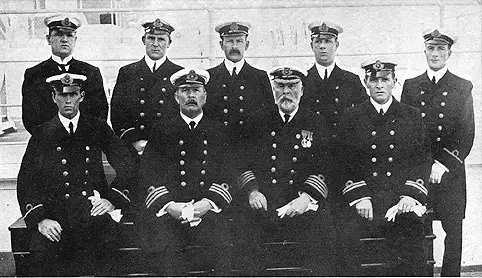

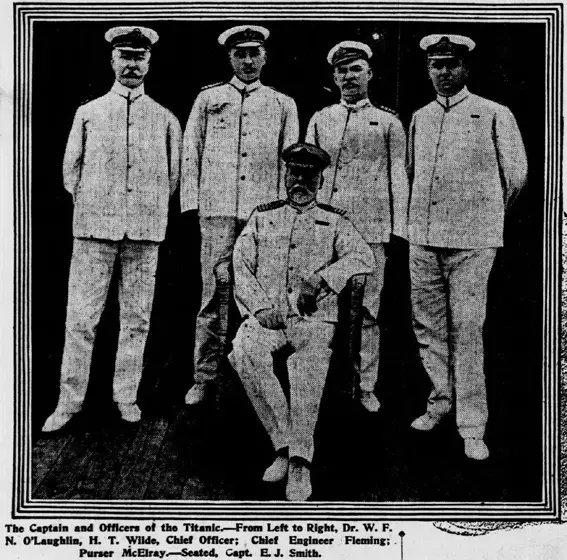

Captain Smith and the Olympic's officers. Standing: First Officer William Murdoch, Purser Hugh McElroy, Purser Claude Lancaster, 2nd Officer Robert Hume. Seated: Captain EJ Smith, Dr O’Loughlin. (Click to enlarge)

Olympic's officers. Standing: Standing: Purser Hugh McElroy

3rd Officer Henry O. Cater, 2nd Officer Robert Hume,

4th Officer David W. Alexander, 6th Officer Harold Holehouse.

Seated: 5th Officer Alphonse Martin Tulloch, Chief Officer Joseph Evans,

Captain Edward John Smith, and 1st Officer William McMaster Murdoch.

(Click image to enlarge)

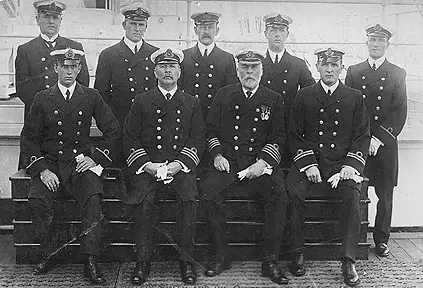

Olympic's officers (slightly different shot from above). Standing: Purser McElroy, Cater, Hume, Alexander, Holehouse. Seated: Tulloch, Evans, Captain Smith, Murdoch.

(Click image to enlarge)

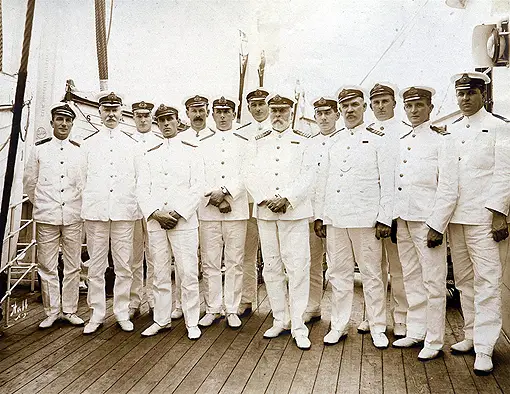

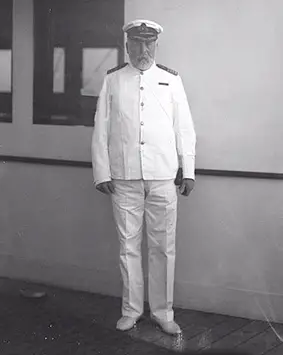

Smith with his Olympic's officers in summer white uniforms.

(8.) (Click image to enlarge)

Captain Smith and his Olympic's officers seated in summer white uniforms, at lifeboat no.6. (8.) (Click image to enlarge)

Another summer group photograph aboard the Olympic, courtesy of Kari Nejak-Bowen, Evening (Sunday) Star (Washington DC) April 28, 1912. (Click image to enlarge)

The Hawke Collision

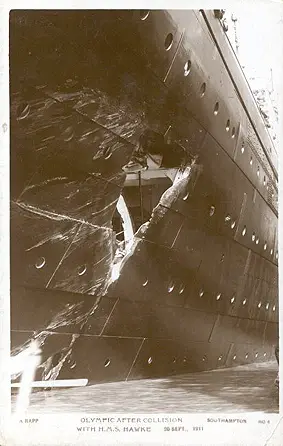

RMS Olympic after the collision

with HMS Hawke.

The first indications of what was to come occurred on Olympic's fifth voyage at 12.46pm on September 20th, 1911, when she had her hull badly damaged in a collision with the Royal navy cruiser HMS Hawke while leaving Southampton. The warship lost her prow and the collision left two of Olympic's compartments filled and one of her propeller shafts twisted. No one was seriously injured or killed and the Olympic was able to return to Southampton under her own power. Although the ship was technically under the control of the harbour pilot, George Bowyer, Captain Smith was still in command of Olympic at the time of the incident. The Admiralty inquiry found that the Olympic had indeed been responsible for the collision but absolved Smith specifically of blame, for his ship was under compulsory pilotage.

According to later testimony, here is the exact exchange of words between Smith and Bowyer in the seconds before Hawke struck Olympic:

Captain Smith: “I do not believe he will go under our stern Bowyer.”

Bowyer: “If she is going to strike let me know in time to put our helm hard-aport.”

Smith did not reply immediately, and a few seconds later Bowyer asks: “Is she going to strike us or not, sir?”

Smith: “Yes Bowyer, she is going to strike us in the stern.”

Bowyer calls out: “Hard-aport!” and helmsman QM Albert Haines just manages to get Olympic’s wheel over hard to his right when Hawke struck.

Some have criticised Smith's apparant delay to inform Bowyer there was going to be a collision. While Bowyer was in command of Olympic at that time, but he depended on others, including Smith, to look out and report to him. Although it was likely already too late by that time to avoid the accident. However author Mark Chirnside points out that Smith was not blamed by the White Star Line, as J. Bruce Ismay testified in 1914:

Questioner: Captain Smith had had a bad accident, had he not, with the Olympic before he took charge of the Titanic?

Ismay: He was run into by one of his Majesty's ships. The Olympic was in charge of a compulsory pilot at the time.

As we outline in the book, the presiding judge, Sir Samuel Evans noted in his December 1911 judgement: ‘that all the orders preceding the collision were given by the pilot and that all his orders were properly and promptly obeyed’.(1914 testimony, courtesy of Mark Chirnside).

We also have a rare insight into Smith's own comments about the Hawke collision, albeit a newspaper article that was printed post-Titanic and hence emphasising the "unsinkable" nature of the ships.:

That Captain Smith believed the Titanic and the Olympic to be absolutely unsinkable is recalled by a man who had a conversation with the veteran commander on a recent voyage of the Olympic.

The talk was concerning the accident in which the British warship Hawke rammed the Olympic.

"The commander of the Hawke was entirely to blame," commented a young officer who was in the group. "He was 'showing off' his warship before a throng of passengers and made a miscalculation."

Captain Smith smiled enigmatically at the theory advanced by his subordinate, but made no comment as to this view of the mishap.

"Anyhow," declared Captain Smith, "the Olympic is unsinkable, and the Titanic will be the same when she is put in commission."Why," he continued, "either of these vessels could be cut in halves and each half would remain afloat indefinitely. The non-sinkable vessel has been reached in these two wonderful craft."

"I venture to add," concluded Captain Smith, "that even if the engines and boilers of these vessels were to fall through their bottoms the vessels would remain afloat."

(Washington Times, Tuesday 16th April 1912)

This photograph shows the bridge of the RMS Olympic sometime between the 14th June 1911 and 4th July 1911, during her maiden voyage and shows from left, First Officer William Murdoch, Chief Officer Joseph Evans, Fourth Officer David W. Alexander and Captain Edward J Smith. .

(Click image to enlarge)

However, the incident was problematic for the White Star Line, as the voyage to New York had to be abandoned and the Olympic taken to Belfast for repairs, which took a good six weeks and also slightly delayed the construction of Titanic.

It was not until 11th of December, 1911, that Smith rejoined his ship. Not long after the Olympic threw a propeller blade on the 24th February 1912 after striking a submerged object, while on its way from New York to Southampton and had to return to Belfast for repairs.

Photographs and Film Shot on the Olympic

Due to the publicity surrounding the maiden voyage of the Olympic we fortunately have quite a number of photographs and even some movie footage of the ship and its captain.

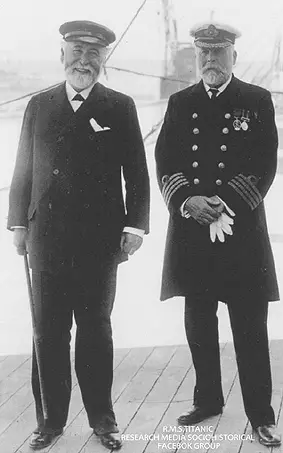

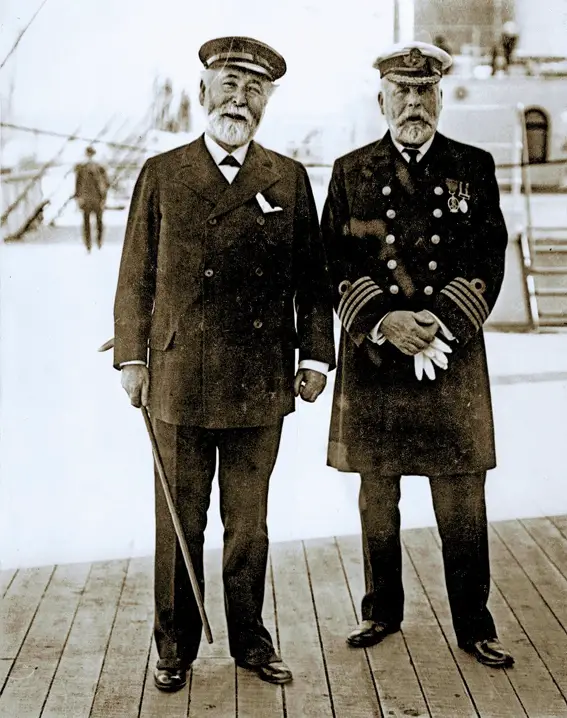

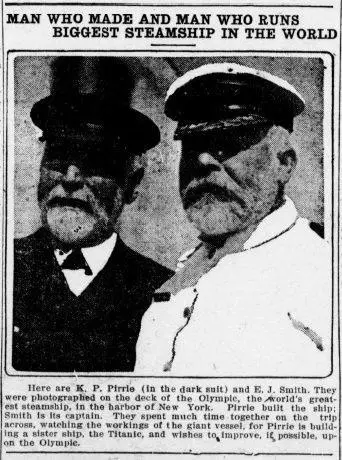

Firstly there is a series of photographs on the boat deck of the Olympic with Lord William J Pirrie, chairman of Harland and Wolff, the shipbuilders behind the new Olympic class ships, taken during June 1911.

Above and right: Captain Smith on the boat deck of RMS Olympic, June 1911, with Lord William J Pirrie, chairman of Harland and Wolff (click to enlarge).

An alternate photograph of Smith posing with Lord Pirrie aboard the Olympic.

(Click image to enlarge)

Smith again with Lord Pirrie,

this time in New York and in his summer uniform.

According to The Titanic and Silent Cinema by Stephen Bottomore, the footage of Captain Smith was "probably filmed in the summer of 1911 in New York. The ship's name on the bulkhead has been inked out frame by frame to suggest that this was filmed on the Titanic."(56.)

Captain Smith is filmed standing on the starboard side of Olympic's navigation bridge.

Rare film footage: Captain EJ Smith, in summer uniform, on the starboard wing bridge of the R.M.S. Olympic in 1911. (Click to play the video.)

There are two shots of Captain Smith. The first is him, in summer uniform, on the starboard wing bridge of the Olympic. The name on the bulkhead has been later inked out frame by frame to suggest it was filmed on Titanic. Smith is noticeably uncomfortable about being filmed and wanders around nervously, smiling at the camera at the end.

The second is a medium close up of Captain Smith, also on the starboard wing bridge, with the wheel house behind him and to his left is a pedestal for a pelorus, a dial with a sighting device on top enables one to sight an object and determine what angle it is to the bow of the ship. It is a brief shot, in many reels repeated several times to make it appear longer.

The following are some of the many portraits taken of Captain Smith aboard Olympic during 1911, mostly in his summer white uniform:

Image: Ioannis Georgiou's collection

January 1912 - Heavy Seas

On the 17th January 1912, the Olympic arrived in New York having encountered huge seas on the 14th fighting her way through a tremendous gale while west-bound for New York. Captain Smith remembered it as the worst storm he had ever seen in his career and that the wave that tore off the hatch cover was at least 60 feet (18 meters) tall.

In enormous seas, rails along the forecastle were torn off, and the steam winch and anchor windlass were loosened. Despite this brutal punishment, there was no sign of weakness in the Olympic's structure. One of J.Bruce Ismay's port holes was smashed in by the big seas and the steerage and crew areas in the prow were flooded. Ismay had come to New York to attend to business but also to see how the ship coped with rough seas.

The RMS Olympic pictured in heavy seas - artist unknown.

(Click image to enlarge)

Lack of lifeboats

According to a story told by Glenn Marston, Captain Smith was aware of the lifeboat shortage aboard the Olympic - and also his next command the Titanic, as outlined in a curious conversation in a newspaper article published in the New York Post of Friday 19th April 1912:

That Capt. Smith of the Titanic was himself convinced that his vessel did not have enough boats is indicated by the statement of a friend of his, Glenn Marston, printed on Wednesday in the Chicago Record-Herald. Marston, on a recent trip to Europe to investigate public utilities, crossed both ways on the Olympic, then in command of Capt. Smith. He also accompanied the Captain to Belfast to inspect the Titanic when the skipper learned that he had been assigned to the new vessel.

CAPT. SMITH’S FEARS

“Capt. Smith knew that the Titanic did not carry enough lifeboats and rafts,” said Marston. “When he went to Belfast, where the Titanic was built, just after he was notified that he was to take command, he noticed the small number of life-saving devices and was not satisfied, he told me. I got into a discussion with him when I was returning on the Olympic, on what I believe was his last trip on that ship before he took command of the Titanic.

“I noticed the small number of lifeboats and rafts aboard for the heavy passenger carrying capacity of the ship, and remarked upon it to Capt. Smith.

“’Yes,’ he said, ‘if the ship was to strike a submerged derelict or iceberg that would cut through into several of the water-tight compartments, we have not enough boats or rafts aboard to take care of more than one-third of the passengers. The Titanic too, is no better equipped. It ought to carry at least double the number of boats and rafts it does to afford any real protection to the passengers. Besides, there is always danger of some of the boats becoming damaged or swept away before they can be manned’”

Marston asked Capt. Smith why the company took such a chance and whether it was to save money.

LIFEBOATS UNDERRATED

“No,” the captain is quoted as replying. “I don’t think its from motives of economy as the additional equipment would cost only a trifle when compared to the cost of the ship, but the builders nowadays believe that their boats are practically indestructible as far as sinking goes, because of the water-tight bulkheads, and that the only need of lifeboats at all is for purposes of rescue from other ships that are not so modernly constructed or to land passengers in case of the ship going ashore. They hardly regard them as life-saving equipment.

“Personally, I believe that a ship ought to carry enough boats and rafts to carry every soul aboard it. I have followed the sea now for forty years and have attributed my success in not having an accident, until we were rammed by the Hawke in the Solent at Southampton, and I was exonerated in that case, to never taking a chance.

“I always take the safe course. While there is only one chance in a thousand that a ship like the Olympic or Titanic may meet with an accident that would injure it so severely that it would sink before aid would arrive, yet, if I had my way, both ships would be equipped with twice the number of lifeboats and rafts. In the old days it was different from to-day, with the mergers and Trusts in the steamship business. Now the captain has little to say regarding equipment. All of that has been taken out of his hands and is taken care of at the main office.

(New York Post, Friday 19th April 1912)

Olympic Lifeboat Tests

During the British Titanic Inquiry in 1912, it was revealed how Captain Smith was progressively checking and testing the Olympic's lifeboats which the Solicitor-General concluded, based on Smith's reports, that "it would appear as though two boats were selected on each occasion, but they do not take the same two boats, and by taking different boats it does appear as though there was a gradual testing of different people." He reported at the inquirt, reading from the documentation:

19233. (Solicitor-General) This is the first one, “Southampton, 15th December, 1911. “It gives the date when he left outwards and left homewards. He then reports the conduct of the officers and crew, the chief officers, and then “General Remarks.” I find on the 15th December, 1911, he was reporting, “Boats Nos. 1 and 3 lowered and crews exercised at Southampton. All davits and falls in good order.” Then the next return, which is on the 6th January, 1912, he reports, “Boats Nos. 6 and 8 lowered before leaving Southampton, and crews exercised. All davits and falls in good order and condition.” The next one is the 31st January, 1912, “Before leaving Southampton Nos. 10 and 12 boats lowered and crews exercised. All davits and falls in good order.” The next is the 28th February, 1912, the last but one. He says, “February 6th, Boats Nos. 9 and 11 lowered, and crews exercised. Everything working well. Davits and falls in good order.” Then the last one is the 30th March, 1912. He puts, “Tuesday, 22nd March.” that, as I see from high up on the page, is the day before he left New York: “Nos. 13 and 15 swung out, lowered, and crews exercised. All davits and falls in good order.” (British Inquiry)