Side Menu:

Second Officer C.H.Lightoller

- World War Two & Dunkirk

The playful side of Lightoller never disappeared.

Photographed in later years in uniform with a pipe.

(Click image to enlarge)

Just before the Second World War started in 1939, when Lightoller was aged 65, he was used by the British Admiralty to secretly photograph and sketch the German coastline in his Sundowner motorboat, providing useful information to be used in an increasingly inevitable conflict. It was a husband and wife effort, with Sylvia on deck knitting or reading a book while Lightoller worked below decks. On one occasion they were stopped by a German patrol boat:

As they had planned, Sylvia was on deck looking simply like the dutiful wife attending to standard domestic chores, and she shouted down below to Charles that a patrol boat was approaching. This gave him adequate time to hide away his camera and his most recent sketches and notes. The Germans climbed aboard and started shouting to see the captain. Charles complied, coming up the stairs with a gin bottle in hand and a stagger to his steps. The ruse worked. The sight of the drunken, 65-year-old sailor was enough for the Germans to leave shortly thereafter, somewhat bemused and disgusted at the spectacle, and the immediate danger was over. (61.)

War finally broke out on the 1st of September, and 3 days later, on September 4, 1939, their youngest son, Herbert Brian, was shot down during the Blenheim Bomber 107 Squadron Raid near Wilhelmshaven. The 107 Squadron lost four of its five planes on the raid and Brian was among the first British casualties of the Second World War. Leaving for Wilhelmshaven, where the German cruiser Emden had been spotted during reconnaissance operations, it is believed that Brian’s Blenheim was shot down by anti-aircraft fire. Brian and the crew were initially buried with full military honours in the Naval Garrison Cemetery in Wilhelmshaven but were later exhumed and reburied in the British Military Cemetery at Oldenburg (Sage) in Germany.

His death must have been a terrible shock to Herbert and served as a motivation behind his next heroic effort.

Dunkirk

Nine months later, at 5.00pm on the 31st of May 1940, Charles Lightoller with his son Roger, left Cubitt’s Yacht Basin in Chiswick for Ramsgate. The Sundowner had been requisitioned for a daring operation to save as many soldiers as possible from France, in particular Dunkirk. However Lightoller was not about to let his boat go without him - he agreed only on the basis that he would captain her.

Lightoller (right) with his eldest son Roger aboard the Sundowner, sometime after Dunkirk. (Click image to enlarge)

So at 10am on the 1st of June 1940, along with his eldest son Roger and an 18-year-old Sea Scout named Gerald Ashcroft, Lightoller sailed across the English Channel. After rescuing the crew of the motor cruiser ‘Westerly’ that was on fire, Lightoller drew alongside the destroyer ‘HMS Worcester’ and started to take on soldiers, managing to fit about 130 men in a boat that had previously never carried more than 21. On the return journey they came under heavy fire all the way back, being dive-bombed by enemy aircraft and dodging mines. Lightoller took evasive action based on what he had learned about how fighter aircraft attack from his son Brian. It took more than three long hours for the Sundowner to reach Ramsgate Harbour, but all 130 were safely disembarked.

As with many things in Lightoller's life, the number of men he rescued is uncertain as sources vary slightly. The Association of Dunkirk Little Ships says, "Sundowner embarked 130 men." A member of Lightoller's crew says he "counted 129 troops aboard." In a radio interview, Lightoller says, "We tallied up 130." A commemorative plaque outside Lightoller's former home in Richmond says he "rescued 127 men." Stenson (2011) says, "Including the three-man crew and the five men rescued from the [sinking ship] Westerly she now had exactly 130 on board."

Note: I recommend watching the film in "Full Screen Mode," with speakers/headphones turned on for the full experience. To activate "Full Screen Mode," you need to click on the video title which will take you to YouTube and then click on the lower right hand box.

For a full transcript of the radio interview see the article here.

Lightoller later described his experience in more detail in a 'yarn' given at an Little Ship Club meeting in St Stephen's Tavern in 1942:

During the whole embarkation we had quite a lot of attention from enemy planes, but derived an amazing degree of comfort from the fact that the Worcester’s Anti-Aircraft guns kept up an everlasting bark overhead. Casting off and backing out we entered the Roads again, there it was continuous and unmitigated hell. The troops were just splendid and of their own initiative detailed look-outs ahead, astern and abeam for inquisitive planes as my attention was pretty wholly occupied watching the steering and passing orders to Roger at the wheel. Any time an aircraft seemed inclined to try its hand on us, one of the look-outs would just call quietly, “Look out for this bloke, skipper”, at the same time pointing. One bomber that had been particularly offensive, itself came under the notice of one of our fighters and suddenly plunged vertically into the sea just about fifty yards astern of us. It was the only time any man ever raised his voice above a conversational tone, but as that big black bomber hit the water they raised an echoing cheer.

My youngest son, Pilot Officer H. B. Lightoller (lost at the outbreak of war in the first raid on Wilhelmshaven) flew a Blenheim and had at different times given me a whole lot of useful information about attack, defence and evasive tactics (at which he was apparently particularly good) and I attribute, in a great measure, our success in getting across without a single casualty to his unwitting help. On one occasion an enemy machine came astern at about 100 feet with the obvious intention of raking our decks. He was coming down in a gliding dive and I knew that he must elevate some 10 to 15 degrees before his guns would bear. Telling my son “Stand by”, I waited till as near as I could judge, he was just on the point of pulling up and then “Hard a-port”. (She turns 180 degrees in exactly her own length). This threw his aim completely off. He banked and tried again. Then “Hard a-starboard”, with the same result. After a third attempt he gave it up in disgust. Had I had a machine gun of any sort, he was a sitter – in fact there were at least three that I am confident we could have accounted for during the trip.

For a full version of this 'yarn' please see the full transcript here.

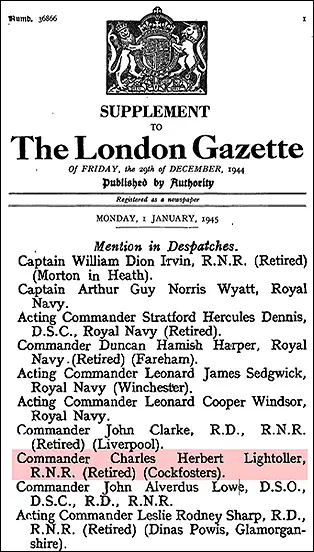

Lightoller's efforts are mentioned in Dispatches in

the London Gazette, 29 December 1944.

Interestingly, Charles’s second son, Second Lieutenant R. T. Lightoller, had been evacuated from Dunkirk 48 hours previous to Charles arriving. Also, the 18 year old Sea Scout Gerald Ashcroft who went to Dunkirk with Lightoller in 1940 became a naval officer and in 1944 commanded LCT 507, 20th Flotilla during the Normandy landings.

After such an heroic effort, Lightoller returned to duties as an active member in the Home Guard. The Sundowner was requisitioned for defence roles throughout the war and incurred damage to her stern. For his actions during the evacuation, Charles Lightoller received a mention in despatches in 1944.

Further sacrifice was to occur however, when his son Roger lost his life in the Royal Navy along the North France coastline during the Germans raid of Granville on March 9, 1945.

Lightoller in 1944 as skipper of a small armed vessel on patrol during WWII.

Boatyard

Now in his 70s, an elderly Lightoller took over a small boat building business named "Richmond Slipways" on the Thames in East Twickenham in 1947, in partnership with an old friend and his only remaining son, Trevor. He lived there on the boatyard at 1 Duck's Walk with his wife Sylvia, opposite the site of the old Tudor palace. "Richmond Slipways" mostly repaired police boats.

Richmond Slipways circa 1945-1965 (Photograph: Getty Images)

If this website has been of some help, please consider supporting it with a coffee

to ensure it can continue. It can be anonymous. Anything helps!: