Side Menu:

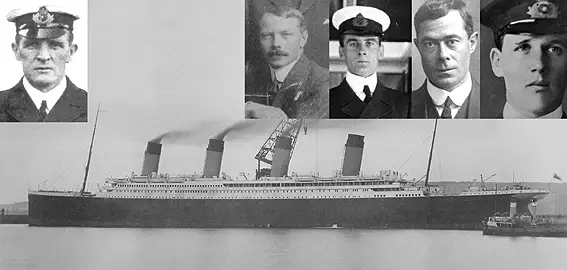

Fifth Officer Harold Lowe

- R.M.S. Titanic

Belfast

When 29-year-old Harold Lowe arrived in Belfast he considered himself a "stranger" later saying: "I was a total stranger in the ship and also to the run." As for the officers "most of them had met each other before... Some of them came from the same ship, but which I do not know. Some of them came from the Oceanic." (US Inquiry, Day 5). While fellow junior officers Pitman and Moody had indeed previously been aboard the Oceanic, Lightoller had been on the Majestic, while Smith, Wilde and Murdoch had come from the Olympic, Titanic's sister ship.

Fifth Officer Lowe arrived aboard Titanic with the other junior officers (Pitman, Boxhall and Moody) on the 27th and reported to Chief Officer Murdoch.

Lowe arrived aboard Titanic at noon on the 27th:

"It was the 26th that I left Liverpool, and I joined the Titanic on the 27th. I think you will find that correct. I distinctly remember now I received a telegram from the superintendent; word to the effect that I was to report to the office at 9 o'clock on the morning of 26th…You see we had to call there for the ticket, and then we went over by night, and we arrived in Belfast the next morning at noon… We left Liverpool at 10 o'clock p. m on the 26th…We arrived at Belfast at about noon on the 27th…We went straight aboard, sir, and reported ourselves to the chief officer."(US Inquiry, Day 5)

Lowe in White Star uniform. (Click to enlarge)

The Chief Officer at the time was William Murdoch, and the captain Herbert Haddock. Part of Lowe's duty was examining the lifeboats - "I was instructed by Mr. Murdoch, the then Chief Officer of the ship to do so." (British Inquiry):

My service, sir, was pretty well general, to do anything we were told to do….Worked out things; worked out the odds and ends, and then submitted them to the senior officer. We are there to do the navigating part so the senior officer can be and shall be in full charge of the bridge and have nothing to worry his head about. We have all that, the junior officers; there are four of us. The three seniors are in absolute charge of the boat. They have nothing to worry themselves about. They simply have to walk backward and forward and look after the ship, and we do all the figuring and all that sort of thing in our chart room. (US Inquiry, Day 5)

Lowe "overhauled" the lifeboats, personally examining the starboard lifeboat and collapsible:

Mr. Moody and myself and Mr. Pitman and Mr. Boxhall took the port boat - that is, I took the starboard, and they took the port, and we overhauled them; that is to say, we counted the oars, the rowlocks, or the thole pins, whichever you like to call them, and saw there was a mast and sail, rigging, gear, and everything else that fitted in the boats, and plugs, and also that the biscuit tank was all right, and that there were two breakers in the boat, two bailers, two plugs, and the steering rowlock; that is, the rowlock for the oar that you ship aft when there is a heavy sea running, because you can not steer by rudder when there is a heavy sea running, and you put an oar over and you have greater command over an oar and can put more power on it. Everything was absolutely correct with the exception of one dipper. A dipper is a long thin can about that length [indicating] and about that diameter [indicating] - an inch and a quarter diameter - and you dip it down into the water breaker and draw the water. That was the only thing that was short out of our boats, and our boats were, respectively, Nos. 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15, from 1 to 15 - odd numbers. Then the even numbers were on the other side; that is, on the port side of the ship…. We found 14 oars, and, anyhow, a set and a half of oars on one set of rowlocks. That is, if there were six rowlocks, there were nine oars in case of emergency. That is, if an oar got broke there was another extra oar to replace that oar, and there were three spare ones - that is, one and one-half sets. If there were 12 oars in one boat, it was fully equipped. There would be 18 oars altogether - 6 extras - and dippers and everything else. Everything was absolutely correct; I will swear to that... There is a compass... A light, and oil to burn for eight hours; biscuits and water. That is all I can think of at present.(US Inquiry, Day 5)

Sea Trials

Lowe mentions that the sea trials "were due, I think, to be made on the Monday, but there was a bit of a breeze and we had to postpone it because of the breeze. It was squally, in fact."(US Inquiry, Day 5)

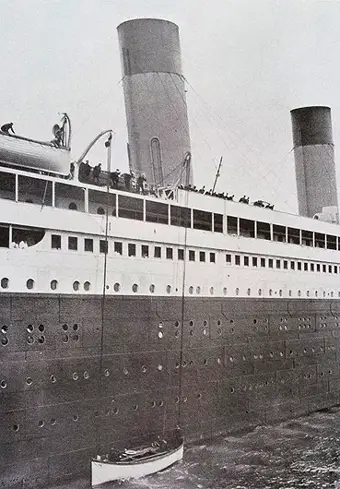

Olympic lifeboat 9 being tested by the Board of Trade

at Southampton, revealing what it must have looked like

when Lowe and crew tested Titanic's lifeboats.

(Click image to enlarge)

When the sea trials finally took place Lowe described the process:

In Belfast Lough; yes, sir. We steamed down. After we had done a few turns and twists we steamed down two hours. I really forget the names of the lightships now, because I don't know that coast, but, roughly we went out two hours on the outward passage and then it took us the same time, naturally, to come back again. That means four hours total steaming. We did take a few extra twists and turns and then came back again…We left, I believe, at 2 o'clock and we anchored somewhere about 6.30 that evening. Altogether, the twists and turns took half an hour, and the steaming, maneuvering the ship, and testing her and all that. That is what I mean by twists and turns. (US Inquiry, Day 5)

Although the Titanic never achieved full speed during the sea trials Lowe stated: "I reckon she could easily do 24 or 25 knots." But during the test "that it was about 20 1/2 or 21" Interestingly Lowe mentioned that the officers were working on a "slip table" to calculate "how many turns of the engine it would require to do so many knots; and all this, and it tapered down... it would be in the chart room" but it was never finished before the sinking. (US Inquiry, Day 5) Overall, Lowe believed that during "the trials the Titanic behaved splendidly and maneuvered very well." (Harold Lowe's sworn disposition to the British Consulate, 1912, courtesy "On Board RMS Titanic," by George Behe)

Once the sea trials were completed Lowe states that they "sent all [Harland & Wolff] workmen ashore by tender to Belfast; and then, … we proceeded on our way to Southampton." Lowe described "fine clear weather, smooth sea, and gentle breeze.(US Inquiry, Day 5)

Southampton Departure

After arriving in Southampton, Lowe had the day shift aboard Titanic: "I was on duty that day, sir; that is, from half past 9... A. m.; until half past 5 p. m. "(US Inquiry, Day 5)

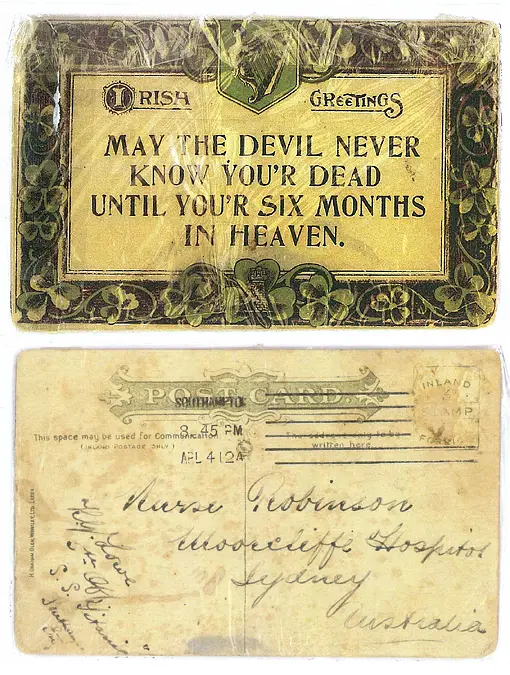

It was possibly after his shift finished that on the 4th of April he posted an unusual piece of correspondence: a postcard entitled an "Irish Greetings" with the phrase, "May the Devil never know you'r dead until you'r six months in heaven." The postcard is addressed to Nurse Robinson at Moorcliff Hospital, Sydney, Australia. The sender is listed as " H.G.Lowe, 5th Officer, SS Titanic, Southampton Eng." and the card postmarked Southampton 8.45pm April 4 1912. the lack of any further message on the card indicates it was likely in reference to an inside comment or joke between Lowe and the Australian nurse. Upon joining the White Star Line in April 1911 he had visited Australia several times, right up until his assignment to Titanic in March 1912. The phrase regarding the Devil is part of an Irish toast: "May your glass be ever full. May the roof over your head be always strong. And may you be in heaven half an hour before the devil knows you're dead." The last phrase indicates enjoying life by avoiding things that may bring trouble, perhaps a life lesson that Lowe had learned from the nurse during his visits to Sydney. According to biographer Inger Sheil, Moorcliff Hospital was the site of the Sydney Eye Hospital at the time Lowe sent this card, although it was known for injured sailors to also be treated there, as it was close to the docks, with White Star Line ships calling at the Dalgety Wharf in Millers Point. In 2014 the postcard was put up for auction at Bonhams in London,

The front and reverse of a postcard written by Lowe and posted in Southampton while aboard the Titanic on the 4th of April, 1912, to a nurse in Sydney, Australia.

(Courtesy of Kari Nejak-Bowen/Bonhams)

(Click image to enlarge)

On sailing day, Wednesday April 10th, before breakfast Lowe was involved in a lifeboat test "it was for the Board of Trade….I was in one and the sixth officer was in the other." He explained:

After the general muster at 8.30 - on the 10th that was - we manned two boats, Mr. Moody, the sixth officer, and myself…On the starboard side, because you must remember that we were laying alongside of a wharf, now. And we were sent away in two boats, with two crews, naturally, and we turned around the dock in a row and then came back and got hoisted up…I should say 20 minutes to half an hour... There is not only practice in the rowing of the boats but there is also practice in the lowering away and clearing. We were lowered down in the boats with a boat's crew. The boats were manned, and we rowed around a couple of turns, and then came back and were hoisted up and had breakfast, and then went about our duties.(US Inquiry, Day 5)

At midday Titanic departed from Berth 44 in Southampton, where Lowe could be found on the bridge manning the telephones and relaying messages and commands given by Pilot George Bowyer to his fellow officers.

Queenstown

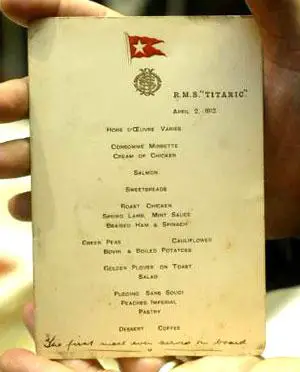

The Titanic menu Lowe sent to his fiancée,

Ellen Whitehouse. (Image: dailyecho.co.uk)

During Titanic's stopover in Queenstown, Ireland, Lowe took the opportunity to send off a special item to his fiancée, Ellen Whitehouse. He had commandeered a menu from the Titanic’s first meal service, and figured she might be interested in seeing the fine food choices that were available on the luxury liner. On the bottom Lowe had scrawled: "This is the first meal ever served on board."

The menu - dated 2 April, 1912 - offered a choice of consommé mirrette, sweetbreads, spring lamb and braised ham. Ellen treasured this as a fine keepsake, and many years later in 2004 it was sold at auction at Henry Aldridge and Son in Devizes, Wiltshire, for an amount variously reported as ₤28,000, ₤45,000, and even ₤78,000.

Cabin and Duties

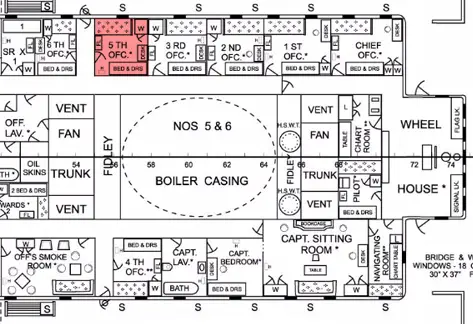

At the US Inquiry, Lowe went on to explain the position of his cabin: "I lived, where it says "Fifth Officer….There were the chief officer and the first officer - the first, second, and third and sixth officers on that side. Then on the opposite side of the ship - that is, the starboard side - the captain lived and the fourth officer, namely, Mr. Boxhall." (US Inquiry, Day 5)

Fifth Officer Lowe's cabin marked in red.

(Plan: Encyclopedia Titanica)

Lowe soon settled into the routine of being at sea. He described it thus: "It is the White Star routine. The White Star Co. have regulations, just the same, in fact, as the Navy, and we all know exactly what to do, how to do it, when to do it, and where to do it. Everybody knows his business, and they do it. There is no hitch in anything… We have the log every two hours, and we are all the time navigating. We do not take observations once a day. We perhaps take 25 or 30 observations a day." (US Inquiry, Day 5)

In his role as Fifth Officer, he was responsible for two, four-hour watches each day.

As a junior officer he shared his watches with Third Officer Herbert Pitman. This included "dog watches" a shift in a maritime watch system that is half the length of a standard watch period which is formed by splitting a single four-hour watch period between 16:00 and 20:00 (4 pm and 8 pm) to form two two-hour dog watches, with the "first" dog watch from 16:00 to 18:00 (4 pm to 6 pm) and the "second" or "last" dog watch from 18:00 to 20:00 (6 pm to 8 pm). The logic behind this is to rotate the watches by creating an odd number of watches in a ship's day and hence avoid the same men being assigned the mid-watch (midnight to 4 am) every night.

Aboard Titanic in practice this meant:

|

Regular Sea Watches |

|

|

First watch |

8pm - Midnight |

|

Middle watch |

Midnight - 4am |

|

Morning watch |

4am - 8am |

|

Forenoon watch |

8am - Noon |

|

Afternoon watch |

Noon - 4pm |

|

First Dog Watch |

4pm - 6pm |

|

Second Dog Watch |

6pm - 8pm |

|

Senior Officer of the Watch |

||

|

Chief Officer Henry Wilde |

2am - 6am |

2pm - 6pm |

|

2nd officer Charles Lightoller |

6am - 10am |

6pm - 10pm |

|

1st officer William Murdoch |

10am - 2pm |

10pm - 2am |

Because of the "Dog Watches", the Junior Officer's watches rotated every two days:

|

Junior Officers - Day 1 |

|

|

4th Officer Boxhall & 6th Officer Moody |

12am - 4am |

|

3rd Officer Pitman & 5th Officer Lowe |

4am - 8am |

|

4th Officer Boxhall & 6th Officer Moody |

8am - 12pm |

|

3rd Officer Pitman & 5th Officer Lowe |

12pm - 4pm |

|

4th Officer Boxhall & 6th Officer Moody |

4pm - 6pm (First Dog Watch) |

|

3rd Officer Pitman & 5th Officer Lowe |

6pm - 8pm (Second Dog Watch) |

|

4th Officer Boxhall & 6th Officer Moody |

8pm - 12am |

|

Junior Officers - Day 2 |

|

|

3rd Officer Pitman & 5th Officer Lowe |

12am - 4am |

|

4th Officer Boxhall & 6th Officer Moody |

4am - 8am |

|

3rd Officer Pitman & 5th Officer Lowe |

8am - 12pm |

|

4th Officer Boxhall & 6th Officer Moody |

12pm - 4pm |

|

3rd Officer Pitman & 5th Officer Lowe |

4pm - 6pm (First Dog Watch) |

|

4th Officer Boxhall & 6th Officer Moody |

6pm - 8pm (Second Dog Watch) |

|

3rd Officer Pitman & 5th Officer Lowe |

8pm - 12am |

Sunday April 14th 1912

On the Sunday Lowe worked "from noon until 4 p. m…. Off for two hours; and then on again.... I worked the course from noon until what we call the "corner"; that is, 42 north, 47 west. I really forget the course now. It is 60º 33 1/2' west - that is as near as I can remember - and 162 miles to the corner." (US Inquiry, Day 5)

Lowe used a "chronometer" to ascertain the 8pm position. He calculated that:

"Her speed from noon until we turned the corner was just a fraction under 21 knots…I used the speed for the position at 8 o'clock, and got it by dividing the distance from noon to the corner by the time that had elapsed from noon until the time we were at the corner…we were working at our slip table, and that is a table based upon so many revolutions of engines and so much per cent slip; and you work that out, and that gives you so many miles per hour. This table extended from the rate of 30 revolutions a minute to the rate of 85 and from a percentage of 10 to 40 per cent slip; that is, minus. We were working it all out, and of course it was not finished."(US Inquiry, Day 5)

Lowe's impression of Titanic - An original watercolour of Titanic at sea painted by Harold Lowe. Image: Henry Aldridge & Son. (Click image to enlarge)

This information was put on the captain's chartoom table:

From 6 to 8 I was busy working out this slip table as I told you before, and doing various odds and ends and working a dead-reckoning position for 8 o'clock p. m. to hand in to the captain, or the commander of the ship…I handed him the slip report…On his chart-room table…We simply put the slip on the table; put a paper weight or something on it, and he comes in and sees it. It is nothing of any great importance….so that the position of the ship might be filled in the night order book.(US Inquiry, Day 5)

As for speed "the highest I remember was 75 revolutions per minute." (British Inquiry)

Lowe remembered seeing something about ice in the chartroom about the "slip table" after 2pm on Sunday:

Sometime after 2, I suppose…There was a slip that showed the position of the ice, the latitude and longitude; but who reported it, or anything else, I do not know anything about it….it was in our own chart room….it was stuck in the frame…The frame is just above the table, and I saw it there…And the word "ice" was above it…When you come to think of it, it could not have been anything else but wireless…I just looked at it casually…I think it was to the northward of our track." (US Inquiry, Day 5)

He later at the British Inquiry described the paper with "ice" written on it as a "square chit of paper about 3 x 3….. On our chart room table… The officers chart room table, and the word “ice” was written on top and then a position underneath….That was the only information I saw regarding ice." (British Inquiry)

Here we see a discrepancy - in the US he described it noticing the chit "sometime after 2" (US Inquiry) but changed this to "shortly after 6." in England. (British Inquiry)

Later during the British Inquiry, Boxhall was referred to this "chit" and responded "Yes. The mentioning of it has refreshed my memory, and I remember writing it out... and it is the position of the “Caronia’s” ice. I copied it off the notice board to save taking the telegram itself down. I copied it on a chit and took it into the Captain’s chart room, and put it on the chart, and that is the ice that I must have put down between 4 and 6 in the evening."

But in this Boxhall described the chit being placed in the "Captain's chartroom" while Lowe, both in the US and UK had described it as being "in our own chart room" (US Inquiry) and "officers chart room table" (British Inquiry).

Nonetheless, the details found on this chit were probably not deemed important for one simple reason:

I ran this position through my mind, and worked it out mentally, and found that the ship would not be within the ice region during my watch, that is, from six to eight. (British Inquiry)

See also...

Next... Evacuation