Side Menu:

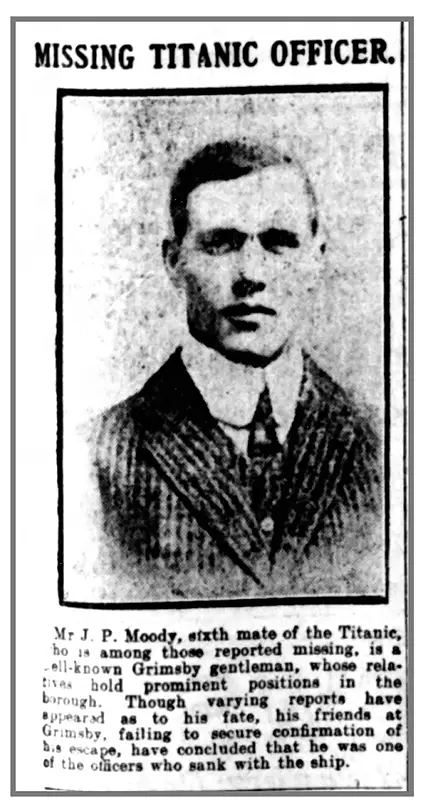

Sixth Officer James Moody

- Death

Second officer Lightoller last saw

Moody "on top of the quarters clearing

away the collapsible boat on the

starboard side"

James Moody's body was never found, so an exact cause of death cannot be established. We do know that he was last seen helping to launch collapsible A and there are two primary witness accounts of this:

Second Officer Lightoller

Second Officer Lightoller was questioned at the British Inquiry regarding Moody and this is what he said: "I do not remember seeing Mr. Moody that night at all, though I am given to understand, from what I have gathered since, that Mr. Moody must have been standing quite close to me at the same time. He was on top of the quarters clearing away the collapsible boat on the starboard side, whilst Mr. Murdoch was working at the falls. If that is so, we were all practically in the water together." (British Inquiry)

Lamp Trimmer Samuel Hemming

Lamp Trimmer Samuel Hemming

remembers speaking to Moody

at collapsible A

Lamp Trimmer Samuel Hemming remembers speaking to Moody at collapsible A: "I rendered up the foremast fall, got the block on board, and held on to the block while a man equalized the parts of the fall. He said, "There is a futterfoot in the fall, which fouls the fall and the block." I says, "I have got it;" and took it out. I passed the block up to the officers' house, and Mr. Moody, the sixth officer, said: "We don't want the block. We will leave the boat on deck." I put the fall on the deck, stayed there a moment, and there was no chance of the boat being cleared away, and I went to the bridge and looked over and saw the water climbing upon the bridge. I went and looked over the starboard side, and everything was black. I went over to the port side and saw a boat off the port quarter, and I went along the port side and got up the after boat davits and slid down the fall and swam to the boat and got it." (US Inquiry)

How He Died

As his body was never recovered we do not know how he died. Jemma Hyder and Inger Sheil explored the possibilities:

There is a possibility that James - relieved of his duties by the words ‘every man for himself’ - left the forward area of the boat deck where men were still struggling to free A and headed aft towards the brief, illusionary safety of the stern where many others were gathering. More likely, though, he was still either on the roof where Hemming had seen him, or had jumped down to the level of the boat deck to work on A from there. Lightoller, who claimed later not to have seen his junior colleague all evening, seems to have made some inquiries as to what had become of the youngest officer. However, as Lightoller knew Hemming quite well, it is possible and even probable that he derived his information from the lamp trimmer. If he had confirmation from an additional source, it is not known.

If he did remain on the forward part of the boat deck working on A, struggling with the falls on a sloping deck amidst a crowd of people, James soon found himself engulfed by the on-rushing sea. ‘I do not remember seeing Mr. Moody that night at all,’ Lightoller later explained, ‘although I am given to understand, from what I have gathered since, that Mr. Moody must have been standing quite close to me at the same time. He was on top of the quarters clearing away the collapsible boat on the starboard side, whilst Mr. Murdoch was working at the falls. If that is so, we were all practically in the water together.’

The combination of suction, water rushing into the hull of the ship and debris made this a lethal place to be in. Lightoller and Gracie were both pulled under by suction, Lightoller becoming pinned against the fiddley gratings. A combination of a fortuitous blast of air and his lifejacket helped him. Gracie, too, was buoyed by his lifejacket and regained the surface. Whether Moody was wearing his jacket is not known.

Whatever fate befell him, it was not a gentle way to die. The forward funnel fell, crushing those in its path, and it is possible James was one of those who suffered this quick - if terrifying - death. Debris had buffeted those survivors who were able to gain the comparative safety of the overturned B or A, which had floated free. Later they would find bruises and abrasions all over their bodies. Another possibility is that he was either tangled in falls or, like Lightoller was briefly, dragged into or against one of the open vents, drowning when unable to break free. He was not among the handful of swimmers who made it to a lifeboat or were pulled from the sea. If he made it away from the sides of the ship, he was one of those who waited in vain for assistance. ()"On Watch" - Nautical-papers.com, 2002 by Jemma Hyder and Inger Sheil)

There has been speculation as to why Sixth Officer Moody did not take the opportunity to leave the sinking ship, summed up in the following passage:

Moody's reasons for not leaving Titanic when he had the opportunity to do so can only be a matter of conjecture. When Lowe told him to take command of No. 16 there were still lifeboats to be launched – possibly he had every intention to "get in another boat". Other factors might have intervened – Wilde or Murdoch could have set him to work on the starboard boats. There is also an unknown psychological element - he might have been attempting to prove something to his fellow officers, his family, or even himself. More probably, the sense of duty both innate and instilled in him through his training might have prevented him leaving, even if he was ordered to do so by an officer more senior than Lowe; the same concept of duty and honor that would see tens of thousands of his generation slaughtered on the fields of Flanders a few short years into the future. Quite simply, he might have felt that staying with the ship was the right thing to do. There was nothing passive or simply stoic about his apparent acceptance of his fate – from what we know, to the very end he was engaged in trying to find practical ways to save lives and fulfill what he perceived as his duty to crew and passengers. (Bridge Duty, Officers of the RMS Titanic, Inger Sheil & Kerri Sundberg, 1999)

"Head Injury"

Junior wireless operator Harold Bride

allegedly mentioned Moody with a

"head injury" many years later

Some conjecture has been put forward regarding officers being the suicide victim. For instance, in a 1954 interview with Harold Bride by Ernest Robinson and related in Richard Edkins Dalbeattie website, he mentions that Bride saw ‘Murdoch lying motionless in the water and Moody appeared to have suffered a heard injury.’ (paraphrased from Richard Edkin’s text, Murdoch of the Titanic website) prompting Bride to wonder at the time if it was Sixth Officer Moody who had been shot. Yet, as already considered, Bride was most likely on the port side and never on the starboard side. Also, while under oath, he testified to the fact the he was incapable of identifying any of the officers at the time Titanic sank. George Behe, in analysing this claim, wrote the following:

“As for the webmaster’s [Richard Edkin’s] reference to Sixth Officer Moody (‘was Moody shot?’), this seems to be an attempt to divert attention away from First Officer Murdoch, but the attempt does not hold up to close scrutiny. We know that Titanic’s senior officers -- Smith, Wilde, Murdoch and Lightoller -- were issued Company weapons during the evacuation of the Titanic, and we also know that Fifth Officer Lowe carried his own personal weapon that night; there is absolutely no evidence, however, that Titanic’s remaining junior officers (Moody, Boxhall and Pitman) were armed during the sinking of the Titanic -- which means Sixth Officer Moody probably could not have taken his own life with a revolver even if he had wished to.” (George Behe, First Officer Murdoch and the ‘Dalbeattie Defense’ (11.))

Paul Quinn writes that Moody’s likely cause of death was the same as most of those at collapsible A who were engulfed in “the equivalent of a small tidal wave that pounced on the deck .. abruptly and without warning… Sixth Officer Moody was inundated by the rush of water” (Paul Quinn, Titanic at 2 A.M., p.78 (34.)). Walter Lord also discussed the possible identity of the suicide victim in The Night Lives On: “Who was the officer involved? Could it have been Purser McElroy? Jack Thayer re-called McElroy firing two shots to stop a rush on one of the forward starboard boats, but Thayer did not think it was the last boat. Apart from that, the officers of the Victualling Department were basically ‘housekeepers.’ They were not likely to be in charge of loading and lowering lifeboats, nor would they have the authority to declare ‘Each man for him- self,’ as Rheims noted. Lightoller in his memoirs recalled saying good-bye to the pursers and doctors, who were standing off to one side of the Boat Deck. He specifically praised their quiet courage for staying out of the way while the deck force launched the last boats.

“A far more likely candidate would be one of the three lost officers of the Deck Department. Sixth Officer Moody was on the scene; he was in charge of the party on the roof of the officers’ quarters that cut Collapsible A free. On the other hand, once back on the Boat Deck, he would have come under First Officer Murdoch, who was trying to attach the collapsible to the falls. He then wouldn’t have had the authority to give the order ‘Each man for himself.’” (21.)

Officer Suicide

Murdoch biographer Susanne

Störmer proposes Moody as the

officer who committed suicide

Moody's name is not once mentioned in any of the suicide witness's accounts, neither does he have any apparent motive for suicide and was not present when firearms were supplied to the senior officers during the evacuation.

However, First officer William Murdoch biographer Susanne Störmer surprised many when she wrote an article published on George Behe's Titanic Tidbits website entitled "The Officer Who Shot Himself -- An Alternate Solution" that proposes that Sixth Officer Moody was in fact the officer who committed suicide. Although seeming to offer an explanation as to why Moody cannot be discounted from the names of officers who were possibly involved, her reasoning caused author Inger Sheil to call it "a tremendous disservice...extremely bigoted and one-sided attempt to put the responsibility for the suicide on one candidate, without offering any rebuttal or opportunity to rebut this monstrous editing of history. Whatever injustice Stormer feels has been done to Murdoch, she has repaid it tenfold upon an innocent man." (8.)

Her theory suggests that Moody committed suicide at lifeboat no 16, which was launched at approximately 1:20am -an hour before the ship sank. However this does not tally with evidence that places Moody on the starboard side after the launch of 16, specifically at lifeboats 9, 13 and collapisible A.

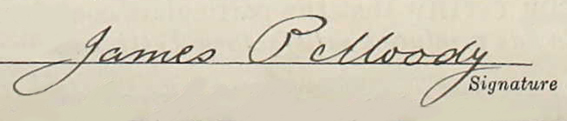

James Moody's signature - which could be interpreted as "Pellody"

"Pellody" and "Missing" news reports

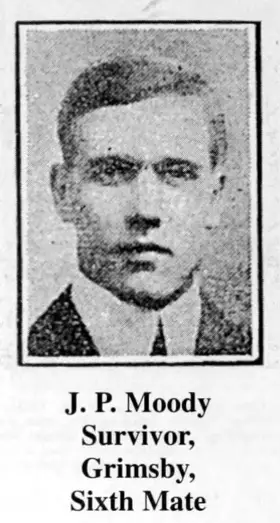

James Moody's signature tended to run the "P" of his middle name into the "M" of his surname which resulted in "James P. Moody" looking similar to or misunderstood as "James Pelloody." This unfortunate fact led to early misunderstandings and heartbreak as the initial reports that came through in the aftermath of the tragedy indicated that James Moody had survived. Consequently an April 19th Daily Sketch article has a photograph of him with the caption "J.P.Moody - Survivor, Grimsby, Sixth Mate"

Sixth Officer James Paul Moody mistakenly

reported as a survivor in the Daily Sketch newspaper,

19 April 1912

This misidentification led to the Moody family believing that he was still alive. An article in the Grimsby Evening News April 1912 had the following:

The Ill-Fated Titanic. Grimbarians on Board the Ship. Anxiety as to their Safety. The Sixth Officer of the great liner is Mr. James Paul Moody, a nephew of Mrs. Arthur Mountain of St James House, with whom he stayed when in Grimsby. Mr. Moody who is twenty-four years of age had previously served for the space of some ten months on board the Oceanic of the same company. A letter was received from Mr. Moody only the day before the Titanic sailed from Southampton, and it is evident that Mr. Moody as was only naturally to be expected, was looking forward with keen interest to this, the maiden voyage of the world's largest passenger liner.

According to Inger Sheil "[James Moody's] father was still alive at the time of the Titanic sinking, and was in touch with the WSL [White Star Line] trying to get definitive word on his son's fate - for many days afterwards he was hopeful that James was among the saved." (February 8, 2009, Encyclopedia Titanica message board)

The Scarborough Mercury, Friday 19th April 1912, ran the following article in which it mentions his uncle, likely Arthur Mountain, seeing the name "James Pellody" and hoping it is not his nephew:

Mr. J. P. Moody

Son of Mr. J. Moody

We understand that Mr. J. P. Moody, one of the officers concerning whom no news has been received, is a son of Mr. J. Moody, solicitor, once in practice in Scarborough, and for some years a member of the Scarborough Town Council. The address at Grimsby is that of Mr. Moody's uncle, with whom he lived.

An uncle of Mr. Moody also resides on the South Cliff at Scarborough, and seen on Wednesday afternoon by one of our representatives, Mr. Moody said that the young officer was on board the Oceanic, and he had not heard that he had been transferred to the Titanic. he thought his nephew would have let him know of any change of ship, unless the change was made at the lost moment, so to speak.

Mr. James Paul Moody, the young officer in question, is well known in Scarborough, and he spent part of his holidays with his uncle and part with the latter's sister at Grimsby.

He was a tall, clean-shaven, smart-looking young man, and if his life has been lost great sympathy will be felt for his relatives. The uncle, when seen by our representative, said he had looked at the list of passengers and crew to see if there was anyone he knew, and although he saw the name of James Pellody he did not connect it with anyone in Scarborough, least of all his nephew.

''I hope it is not true,'' he said, and our representative could only echo the wish. (Scarborough Mercury Friday 19th April 1912)

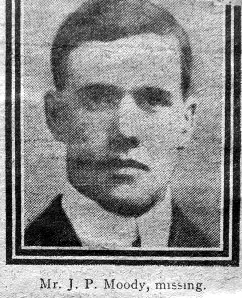

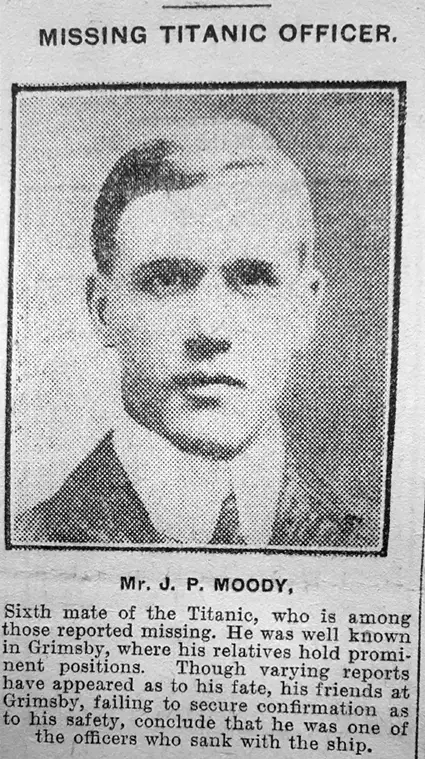

As hope is lost, this article states that "his friends at Grimsby,

failing to secure confirmation as to his safety,

conclude he was one of the officers who

sank with the ship."

Other reports state that the Titanic officer was "missing." However by May it had been confirmed that James Moody had indeed been lost in the disaster. The St James Parish Magazine, May 1912 ran the "Vicar's letter" which said:

The awful tragedy of the Titanic is so much in the minds of us all that I cannot help referring to it in my letter, if only to say how widespread and sincere is the sympathy felt for Mr. & Mrs. Arthur Mountain. Their nephew was Sixth officer of the ill-fated ship and he made his home in St. James House. His brother, C. W. Moody is organist at St. Augustine's where a beautiful memorial service was held. There can be no doubt that every officer, engine man and many other men who died, died in the performance of their duty, giving up their lives for others and ''Greather love hath no man than this''. (St James Parish Magazine, May 1912)

Hull Daily News, The Hull Express, Grimsby Express, Hull Morning Telegraph, and Evening News carried this article on 20 April 1912.

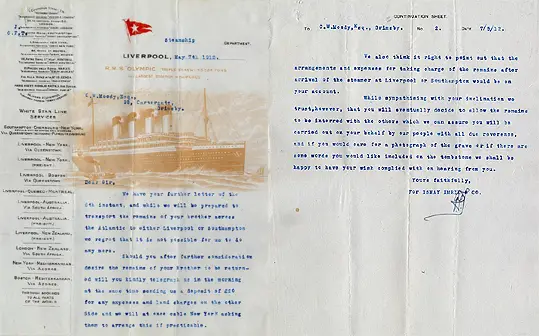

Return of 'Body'

To add insult to injury with confusion over whether James Moody had survived or not, when it was confirmed he had been lost in the disaster the White Star Line (from parent company Ismay Imrie & Co) sent a letter to James' brother, Christopher Moody, asking for a £20 deposit - the equivalent of £2,100 today - to return his body to England and then stated that Mr Moody will also have to meet the remaining costs from there. Alternatively, the company suggests that Mr Moody’s remains be buried in Halifax, Nova Scotia, but they offer to send his family “a photograph of the tombstone”, if they want one. The letter was put for sale at auction by Henry Aldridge & Son in Devizes, Wiltshire in 2015 and was expected to fetch between £20,000 and £25,000.

The letter reads in full:

Dear Sir, We have your further letter of the 6th instant, and while we will be prepared to transport the remains of your brother across the Atlantic to either Liverpool or Southampton we regret that it is not possible for us to do any more. Should you after further consideration desire the remains of your Brother to be returned will you kindly telegraph us in the morning at the same time sending us a deposit of £20 for any expenses and land charges on the other Side and we will at once cable New York asking then to arrange this if practicable. We also think it right to point out that the arrangements and expenses for taking charge of the remains after arrival of the steamer at Liverpool or Southampton would be on your account. While sympathising with your inclination we trust, however, that you will eventually decide to allow the remains to be interred with the others which we can assure you will be carried out on your behalf by our people with all due reverence, and if you would care for a photograph of the grave or if there are some words you would like included on the tombstone we shall be happy to have your wish complied with on hearing from you. Yours faithfully, For Ismay Imrie & Co.

White Star letter asking for a £20 deposit to return Moody's 'body' to England.

(Click image to enlarge)

The reality is that James Moody's body was never recovered. He was the only junior deck officer lost in the disaster. Later a probate report was made listing for his remaining effects: "Moody, James Paul of 136 Fildes Street, Grimsby, Lincolnshire. Ships Officer. Probate registered: London 16th September 1912 to Christopher William Moody solicitors clerk and Margaret Moody spinster. Effects £449.8.8d."

In addition to his probate he was also insured:

Perhaps, as his assets were totalled and the life insurance policy was factored into the final figure, his family had a passing thought for a letter he had written on the 9 January 1910, in which he had gently and with laughter told them he had taken out the policy: “By the way I have just got my precious little life insured, so don’t forget if I snuff out to put in a shout for half the £100 which is all I consider I’m worth!” When the legal minds had settled his estate, totalling his insurance, savings and a legacy from his great uncle, James Moody’s ‘precious little life’ was found to be worth a very precise £458.17.3.(Moody, J. P., Correspondence, Private Collection / "On Watch" - Nautical-papers.com, 2002 by Jemma Hyder and Inger Sheil)

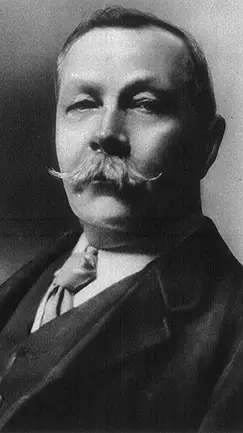

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote that "the

sixth officer went down with the captain"

In a 20th May 1912 The Daily News printed a letter written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle - the Sherlock Holmes creator, criticising George Bernard Shaw's letter about the glamorization of the Titanic disaster. In it Doyle remembers James Moody and his ultimate sacrifice, writing: "The sixth officer went down with the captain, so I presume that even Mr. Shaw could not ask him to do more."

Geoffrey Marcus, who had contacted James's sister Margaret when writing his book "The Maiden Voyage" in the 1960s wrote: "[Chief Officer] Wilde's efforts to avert panic, maintain order and discipline, and get the last of the boats loaded and lowered to the water were valiantly supported by the youngest of the officers, James Moody. Long before this, the latter should by rights have gone away in one of the boats along with the other junior officers. But the seamen left on board were all too few as it was for the work that had to be done. Moody therefore stayed with the ship to the end and was the means of saving many a life that would otherwise have been lost." (The Maiden Voyage, Geoffrey Marcus, 1969)

If this website has been of some help, please consider supporting it with a coffee

to ensure it can continue. It can be anonymous. Anything helps!: