Side Menu:

Second Officer C.H.Lightoller

- Ice Warnings and Collision

Titanic's senior officers, in accordance with IMM (International Mercantile Marine Co) rules worked a "4 hours on and 4 hours off" schedule. In practice aboard Titanic, this meant the following:

Senior Officers’ Watches:

|

Second Officer Lightoller: |

6 am to 10 am |

6 pm to 10 pm |

|

First Officer Murdoch: |

10 am to 2 pm |

10 pm to 2 am |

|

Chief Officer Wilde: |

2 am to 6 am |

2 pm to 6 pm |

This schedule also allowed time for eating, as explained by Lightoller during the British Inquiry: "Lunch is at half-past 12. I relieve the First Officer, who has his lunch at half-past 12, and he comes on deck again about 1 o’clock or five minutes past; then I have mine."(24.)

Caronia Ice Warning

Titanic continued sailing in "what is known as the outward southern route"(24.) (Lightoller, British Inquiry) and it was during this break at lunch on April 14, 1912, that Lightoller first heard about ice ahead. There was a protocol for ice messages, which Lightoller explains:

It is customary for the message to be sent direct to the bridge. If addressed “The Captain,” or “Captain Smith,” it is delivered to Captain Smith personally, if he was in the quarters or about the bridge. If Captain Smith is not immediately get-at-able, if not in his room or on the bridge, it is then delivered to the senior officer of the watch. Captain Smith’s instructions were to open all telegrams and act on your own discretion.(24.)

At the US Inquiry he described the first ice message he was made aware of:

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. From what ship the message came I have forgotten; but the message contained information that there was ice from 49 to 51….Because I saw it…From the captain…I think it was that afternoon….About 1 o'clock…. On the bridge.

Senator SMITH. With the captain?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. Yes...

Senator SMITH. Who succeeded you as officer of the ship?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. The first officer, Mr. Murdoch.

Senator SMITH. Did you communicate to him this information that the captain had given you on the bridge?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. I communicated that when I was relieving him at 1 o'clock.

Senator SMITH. What did you tell him?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. Exactly what was in the telegram.

Senator SMITH. What did he say?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. "All right."(25.)

Later on Day 5 of the US Inquiry, Lightoller explained further about the telegram.

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. The commander came out when I was relieved for lunch, I think it was. It may have been earlier; I do not remember what time it was. I remember the commander coming out to me some time that day and showing me a telegram, and this had reference to the position of ice... An approximate position and presumably the maximum eastern longitude.

Senator SMITH. A warning to you, of its proximity?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. Giving the position. No warning, but giving the position - a mere bald statement of fact.

Senator SMITH. Did you regard it as a warning when you got that information?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. We get those repeatedly and various other things, and we regard them as information...

Senator SMITH. What did you do about it?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. Worked approximately the time we should be up to this position.

Senator SMITH. What did you find?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. Somewhere around 11 o'clock.

Senator SMITH. Did you report that fact to anyone?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. I did.

Senator SMITH. To whom?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. The first officer.

Senator SMITH. Murdoch?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. Yes.

Senator SMITH. What time?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. I think when he relieved me at lunch time I spoke about it first. I spoke about it in the quarters, unofficially and I also spoke about it, naturally, when he relieved me at 10 o'clock.(25.)

Later at the British Inquiry, the origin and content of this telegram became clearer:

"Captain Smith came on the bridge during the time that I was relieving Mr. Murdoch. In his hands he had a wireless message, a Marconigram. He came across the bridge, and holding it in his hands told me to read it…. he held it out in his hand and showed it to me. The actual wording of the message I do not remember….It had reference to ice….I particularly made a mental note of the meridians - 49 to 51."(24.)

The Solicitor-General was able to find a record of the message:

13462. (The Solicitor-General.) I think this is the message, and perhaps I can read it to the gentleman and he will tell us if it sounds like it. (To the Witness.) We have independent evidence of a message being sent from the “Caronia.” “West-bound steamers report bergs, growlers and field ice in 42 N. from 49 to 51 W.”(24.)

RMS Caronia, which sent the iceberg warning.

Lightoller also adds that when First officer Murdoch came back from lunch, and Lightoller mentioned the ice report, he could not tell if it was news to him or not. Lightoller also did not have time to calculate how many steaming hours away the ice was.

The ice warning message Lightoller is referring to had actually been sent at 0900 that morning, reporting "bergs, growlers and field ice" which was received from the eastbound Caronia, passing on messages that small and large ice was reported in latitude 42°N, between longitudes 49° and 51°W. Captain Smith had acknowledged the message which was posted on the bridge, most likely in the chart room. Lightoller desribes the chartroom where messages would be posted:

"It consists of the top of a chest of drawers. In those drawers are all the charts, necessarily big drawers, to contain the charts fully laid out, and also drawers for navigational books, instruction books, and so on….A track chart is always lying on that chart room table. …. There are little pads, position pads, and deviation pads, and it is customary to tear off one of these chits and write on the back; and it would have been left on the chart room table, lying on the top of the chart." (British Inquiry(24.))

Later he also mentioned that "we have a notice board in the chart room for the purpose of putting up anything referring to navigation, wireless reports on matters navigational, and it is open for anyone to look at." (British Inquiry(24.)).

After relieving Murdoch for his lunch Lightoller went "below, to my berth or whatever it happened to be. We call the quarters generally below" and was "in and out of the room two or three times during the afternoon. Later on I laid down in the afternoon to sleep, and got up and wrote some letters, or something like that." (US Inquiry(25.))

Final Watch

As per the senior officer's schedule, Lightoller came on the bridge for his final watch of the day: 6pm-10pm, taking over from Chief Officer Wilde.

This watch began just as darkness began to fall. According to Lightoller it went dark at "about half-past six, between half-past six and seven." At which time the wheelhouse blinds are closed " just after sunset." so as quartermaster Robert Hichens testified "I could not see the officer on the bridge. I am in the wheelhouse. I cannot see anything only my compass." After sundown, Lightoller would not have entered the wheelhouse part of the bridge - as he mentions at the US Inquiry " the senior officers can not go inside of the wheelhouse to look at the compass after nighttime; they would be blinded. The junior officers look at it for them. They hold a captain's certificate."(25.)

At some point during Lightoller's watch, likely at the beginning, he must have noted and initialled a footnote in the night order book in regards to ice made by Captain Smith. At the British Inquiry he testified "Speaking about the Commander, with reference to ice, of course, there was a footnote on the night order book with regard to ice. The actual wording I cannot remember, but it is always customary. Naturally, every commander, in the night order book, issues his orders for the night, and the footnote had reference to keeping a sharp look out for ice. That is initialed by every officer." (British Inquiry(24.))

Sixth officer Moody calculated they would reach

the ice at 11pm.

Referring to the Caronia telegram received earlier in the day, he "told one of the junior officers to work out about what time we should reach the ice region, and he told me about 11 o’clock." Lightoller's watch finished at 10 pm and hence believing that he "should not be in the vicinity of the ice before I came on deck again. I roughly ran that off in my mind." (US Inquiry)

During the British Inquiry investigators picked up on this calculation in particular. Lightoller notes that he directed Sixth Officer Moody who made his calculations based on a marconigram " placed on the notice board for that purpose in the chart room" and "the junior officer reported to me, “About 11 o’clock.”(24.) However sometime shortly thereafter "about 7 or 8 o’clock, probably. I really cannot remember, but I know it was after Mr. Moody had given me this time of his" Lightoller made his own calculations:

"I might say as a matter of fact I have come to the conclusion that Mr. Moody did not take the same Marconigram which Captain Smith had shown me on the bridge because on running it up just mentally, I came to the conclusion that we should be to the ice before 11 o’clock, by the Marconigram that I saw…. I roughly figured out about half-past nine. I should not say a mistake, only he probably had not noticed the 49º wireless; there may have been others, and he may have made his calculations from one of the other Marconigrams.""

When first mentioning this at the British Inquiry, Lightoller was questioned as to why he did not question Moody about this:

"I quite see your point, and I had reasons for not doing so. As far as I remember he was busy - what on I cannot recollect, and I thought I would not bother him just at that time. He was busy with some calculations, probably stellar calculations or bearings, and I had run it up in my mind, and I was quite assured that we should be up to 49 degrees somewhere about half-past 9."(24.)

Dinner temperature drop and Captain Smith

At the British Inquiry Lightoller mentions that "Mr. Murdoch goes to dinner at half-past six and relieves me, I think, at five past seven, and I relieved him, I think, at 7.35." meaning the First officer Murdoch took Lightoller's place for half an hour between seven and half-past seven. It was during this time that it was noted the temperature had fallen:

The temperature had fallen considerably. As a matter of fact I happen to know exactly how much because when I relieved Mr. Murdoch after dinner he made the remark to me that the temperature had dropped 4 degrees whilst I was away at dinner….When Mr. Murdoch mentioned it to me as far as I recollect it had fallen from 43 degrees to 39…and then I sent word down to the carpenter about nine o’clock; it was then 33 degrees, and I sent word to the carpenter and to the engine room - for the carpenter to look after his fresh water; that is to say, he has to drain it off to prevent the pipes freezing - and to the engine room for them to take the necessary precautions for the winches.

13596. It is 33 degrees at nine o’clock. That is only one degree above freezing? - One degree, exactly.

13597. What did that circumstance, the serious drop in temperature, indicate to you as regards the probable presence of ice? - Nothing...

13599. (The Commissioner.) That may be, but is it not the fact that when you are approaching large bodies of ice the temperature falls? - Never in my experience, my Lord.

(British Inquiry(24.))

At about 'five minutes to 9' Captain Smith came onto the bridge and was there for "About 25 minutes or half an hour. (British Inquiry(24.))". During the US Inquiry Lightoller first described the conversation, which has become a staple of many films:

Mr. Lightoller: "About five minutes to 9 was the next time I saw him… Probably one of us said "Good evening…. We spoke about the weather; calmness of the sea; the clearness; about the time we should be getting up toward the vicinity of the ice and how we should recognize it if we should see it - freshening up our minds as to the indications that ice gives of its proximity. We just conferred together, generally, for 25 minutes… Capt. Smith made a remark that if it was in a slight degree hazy there would be no doubt we should have to go very slowly…He left the bridge.

Senator SMITH. With any special injunction upon you?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. Yes, sir.

Senator SMITH. What did he say?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. "If in the slightest degree doubtful, let me know."

Senator SMITH. What did you say to him?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. "All right, sir."(25.)

Captain Edward John Smith poses on Titanic's portside of the bridge on the morning of April 10th, in the only known photograph of Smith on Titanic's bridge.

(Click to enlarge)

At the British Inquiry, Lightoller retells the same conversation, with a few more details:

"At five minutes to nine, when the Commander came on the bridge (I will give it to you as near as I remember) he remarked that it was cold, and as far as I remember I said, “Yes, it is very cold, Sir. In fact,” I said, “it is only one degree above freezing. I have sent word down to the carpenter and rung up the engine room and told them that it is freezing or will be during the night.” We then commenced to speak about the weather. He said, “There is not much wind.” I said, “No, it is a flat calm as a matter of fact.” He repeated it; he said, “A flat calm.” I said, “Yes, quite flat, there is no wind.” I said something about it was rather a pity the breeze had not kept up whilst we were going through the ice region. Of course, my reason was obvious; he knew I meant the water ripples breaking on the base of the berg...

I said, “It is a pity there is not a breeze,” and we went on to discuss the weather. He was then getting his eyesight, you know, and he said, “Yes, it seems quite clear,” and I said, “Yes, it is perfectly clear.” It was a beautiful night, there was not a cloud in the sky. The sea was apparently smooth, and there was no wind, but at that time you could see the stars rising and setting with

absolute distinctness... On the horizon. We then discussed the indications of ice. I remember saying, “In any case there will be a certain amount of reflected lights from the bergs.” He said, “Oh, yes, there will be a certain amount of reflected light.” I said, or he said; blue was said between us - that even though the blue side of the berg was towards us, probably the outline, the white outline would give us sufficient warning, that we should be able to see it at a good distance, and, as far as we could see, we should be able to see it. Of course it was just with regard to that possibility of the blue side being towards us, and that if it did happen to be turned with the purely blue side towards us, there would still be the white outline...

The Captain said, “If it becomes at all doubtful” - I think those are his words - “If it becomes at all doubtful let me know at once; I will be just inside.” (British Inquiry(24.))

Additionally, he may have also referenced their speed during their conversation, as Lightoller later added during the British Inquiry:

The Commander mentioned the fact and said: “If it does come on in the slightest degree hazy we shall have to go very slow.” That was when he came on the bridge from 9 to half-past, when we were talking. You were particularly asking if there was any reference to speed. That was the only one. (British Inquiry(24.))

The conversation between Lightoller and Captain Smith as portrayed

in the 1997 film "Titanic."

Possibly due to this conversation with the Captain, Quartermaster Robert Hitchens "heard Mr. Lightoller speak to Mr. Moody and tell him to speak through the telephone to the crow’s-nest to keep a sharp look-out for small ice and growlers until daylight and pass the word along to the look-out man." (British Inquiry(24.)).

Lightoller himself also references this instruction but notes that it was not as a consequence of his conversation with the captain and that he actually got Moody to ring the order twice to the lookouts:

I thought it was a necessary precaution. That is a message I always send along when approaching the vicinity of ice or a derelict, as the case may be…. I told Mr. Moody to ring up the crow’s-nest and tell the look-outs to keep a sharp look out for ice, particularly small ice and growlers. Mr. Moody rang them up and I could hear quite distinctly what he was saying. He said, “Keep a sharp look out for ice, particularly small ice,” or something like that, and I told him, I think, to ring up again and tell them to keep a sharp look out for ice particularly small ice and growlers. And he rang up the second time and gave the message correctly. (British Inquiry(24.))

At the British Inquiry Lightoller mentions that he took up a position on the bridge: "At 9.30 or about 9.30 I took up a position on the bridge where I could see distinctly - a view which cleared the back stays and stays and so on - right ahead, and there I remained during the remainder of my watch. …..I was looking out for ice… Occasionally I would raise the glasses to my eyes and look ahead to see if I could see anything, using both glasses and my eyes."(24.)

When questioned whether the binoculars (glasses) would have assisted him in detecting the ice he replied: "I never have picked up ice at nighttime with glasses…I have never seen ice through glasses first, never in my experience. Always whenever I have seen a berg I have seen it first with my eyes and then examined it through glasses." (British Inquiry(24.))

Just before the end of his watch Lightoller notes that the temperature had reached freezing point (32 degrees Fahrenheit describing this moment as "most probably it was about 10 minutes to 10, when the quartermaster took the temperature of the air and the water by thermometer. (British Inquiry(24.))

During the US Inquiry, Lightoller was asked about why their course was not changed due to the ice ahead. He replied:

"We receive our orders; the routes are laid down. As a matter of fact, these routes are laid down by some of your naval men in the United States, and we adhere to them. We have an ice route. When ice is very prevalent and we know that a lot of ice is coming down from the north and we have been notified of it, we sometimes are instructed to take what we call the ice track, or extreme southern route, coming west…. they come from the company….You get it before you leave port….I have never known the route to be changed by the commander. When we have the absolute position of anything, that is reliable, when the latitude and longitude is given by ship immediately ahead of an iceberg or a derelict - of course, a derelict is still more dangerous than an iceberg - some commanders will alter their course a few miles just to avoid this derelict, particularly if it is in the nighttime. You have the position of that one derelict and if you cross there at nighttime you might haul a little to the southward or northward.(25.)

In the British Inquiry Lightoller goes on to say it was not unusual:

We were making for a vicinity where ice had been reported as you say year after year, and time and again, and I do not think for the last two or three years I have seen an iceberg although ships ahead of us have reported ice time and time again. There was no absolute certainty that we were running into an ice-field or running amongst icebergs or anything else, and it might have been as it has been in years before ice reported inside a certain longitude. (British Inquiry(25.))

Change of Watch: First Officer Murdoch

'Officer of the Watch' First Officer Murdoch on

the bridge of the R.M.S Olympic 1911.

(Click to enlarge)

At 10pm, at the change of his watch, Lightoller describes what happens when First Officer Murdoch appeared to relieve him, in his book:

“The Senior Officer, coming on Watch, hunts up his man in the pitch darkness, and just yarns for a few minutes, whilst getting his eyesight after being in the light; when he can see all right he lets the other chap know and officially ‘takes over.’ Murdoch and I were old shipmates and for a few minutes –as was our custom –we stood there looking ahead, and yarning over times and incidents past and present. We both remarked on the ship’s steadiness, absence of vibration, and how comfortably she was slipping along. Then we passed on to more serious subjects, such as the chances of sighting ice, reports of ice that had been sighted, and the positions. We also commented on the lack of definition between the horizon and the sky –which would make an iceberg all the more difficult to see –particularly if it had a black side, and that should be, by bad luck, turned our way.”(47.)

At the US Inquiry, Lightoller described his conversation with Murdoch, "we remarked on the weather, about its being calm, clear. We remarked the distance we could see. We seemed to be able to see a long distance. Everything was very clear. We could see the stars setting down to the horizon." (US Inquiry) But most notably he also said:

Senator Smith: Did you talk with Mr. Murdoch about the iceberg’s situation when you left the watch?

Mr. Lightoller: No, Sir.

Senator Smith: Did he ask you anything about it?

Mr. Lightoller: No, Sir.(25.)

This turned out to be false. At the British Inquiry he contradicted his testimony by saying that they did indeed talk about ice when he handed over the watch:

I should give him the course the ship was steering by standard compass. I mentioned the temperature - I think he mentioned the temperature first; he came on deck in his overcoat, and said, “It is pretty cold.” I said, “Yes it is freezing.” I said something about we might be up around the ice any time now, as far as I remember. I cannot remember the exact words, but suggested that we should be naturally round the ice. I passed the word on to him. Of course, I knew we were up to the 49 degrees by, roughly, half-past 9; that ice had been reported. He would know what I meant by that, you know - the Marconigram….That we were up around the ice, or something to that effect; that we were within the region of where the ice had been reported. The actual words I cannot remember; but I gave him to understand that we were within the region where ice had been reported " (British Inquiry(24.))

Later during the British Inquiry he was questioned by Thomas Scanlan who represented the National Sailors' and Firemen's Union, about the inconsistency of his testimony as he said they did not talk about ice - twice- while under oath in the United States. Scanlan, after quoting his US testimony asks "You will admit, I suppose, that this is misleading, and, I suppose, you would like to correct it?" Lightoller replies, "Yes, I should."(24.)

Also during the British Inquiry, Lightoller mentioned that he would have reported that Captain Smith had been on the bridge and the conversation that was had between them, although "no orders were passed on about speed." but that he had also "told Mr. Murdoch I had already sent to the crow’s-nest, the carpenter, and the engine room as to the temperature, and such things as that - naturally, in the ordinary course in handing over the ship everything I could think of."(24.)

At the British Inquiry the issue of the two different calculations was raised and Lightoller is asked whether he told Murdoch about the difference. Lightoller said: " I may have done; I really cannot recollect it now, I may have told him that Moody worked it out 11, or I may have told him half-past 9."(24.)

Lawyer, W D Harbinson, who represented third class passengers at the British Inquiry, blames Lightoller for not informing Murdoch of the inconsistent calculations. He said:

When Mr. Murdoch relieved Mr. Lightoller, and he never mentioned the question of the difference of their calculations. I wish to make no reflection on Mr. Lightoller’s capacity or his general conduct, but at the same time I think it my duty to mention this matter to your Lordship that to my mind that was a matter which should unquestionably have been brought to Mr. Murdoch’s attention. That difference in calculation as to the time when they might expect to reach ice was of vital importance, considering the speed at which the “Titanic” was travelling, and yet not one single word about that was said to Murdoch when he relieved Lightoller at 10 o’clock. My Lord, is that consistent with careful seamanship? Is it consistent with careful seamanship that when two officers make a calculation with regard to the time a vessel speeding at, roughly, 22 knots an hour, will be in the vicinity of ice, and there is an hour and half difference, and not one single word of it is mentioned to the senior officer when he comes on watch? (British Inquiry(24.))

At some point Murdoch would have initialed the night order book which at the British Inquiry Lightoller confirmed had the position of the ice as calculated and "he would necessarily initial it."

The very last part of Lightoller's watch would have involved making a note of their speed. At the British Inquiry Lightoller reported that "as a rule, at the end of the watch, the junior officer rings up the engine room and obtains the average revolutions for the preceding watch…We were steaming, as near as I can tell from what I remember of the revolutions - I believe they were 75 - and I think that works out at about 21 1/2 knots the ship was steaming." It is not known whether the speed was discussed with Murdoch, but Lightoller notes that "it is entered up in the logbook, and anyone who wishes to know can merely ask and the information is given him."(24.)

Later in his 1936 BBC broadcast he emphasises that steaming at speed in the region was the norm:

We were steaming that night at a good 22 knots. At ten o’clock, I was relieved as officer the watch by Murdoch, W.M. Murdoch. He and I had been ship mates on many of the ocean greyhounds. I've bulldozed across this ice region times without number both in clear weather and what's more in fog. After the usual formalities, I handed over, wished him joy of a few perishing cold hours and went below. (BBC, 1936)

After Lightoller departed, his job was not completely over. He describes that "I have to go round the decks and see everything is all right; what we call “going round” (British Inquiry(24.)) spending possibly 30 minutes checking out corridors, ladders, and stairwells, looking for anything which might be amiss.

Speed, Mesaba Warning and Unique conditions

It is important to note at this stage, the lack of reduction in speed was, according to Lightoller, not due to wanting to set any records. In his book he writes:

“We were not out to make a record passage; in fact the White Star Line invariably run their ships at reduced speed for the first few voyages. It tells in the long run, for the engines of a ship are very little different from the engines of a good car, they must be run in. Take the case of the Oceanic. She steadily increased her speed from 19 1/2knots to 21 ½ when she was twelve years old. It has often been said that had not the Titanic been trying to make a passage, the catastrophe would never have occurred. Nothing of the kind.”(47.)

At the British Inquiry he also made the point that in any case "we know that in the White Star, particularly the first voyages - in fact you may say pretty well for the first 12 months - the ship never attains her full speed... I can only quote you my experience throughout the last 24 years, that I have been crossing the Atlantic most of the time, that I have never seen the speed reduced." (British Inquiry(24.))

When told at the British inquiry that "was recklessness, utter recklessness, in view of the conditions to proceed at 21 ½ knots" Lightoller replied that "then all I can say is that recklessness applies to practically every commander and every ship crossing the Atlantic Ocean."(24.)

According to Lightoller the tragedy was caused by a freak set of circumstances. He writes: “The disaster was just due to a combination of circumstances that never occurred before and can never occur again. That may sound like a sweeping statement, yet it is a fact.” These conditions are, according to Ligtholler's book:

-“All during that fatal day the sea had been like glass—an unusual occurrence for that time of the year”… “If there had been either wind or swell, the outline of the berg would have been rendered visible, through the water breaking at the base.”

-“never before or since has there been known to be such quantities of icebergs, growler, field ice and float ice, stretching down with the Labrador current.”(47.)

At the British Inquiry Lightoller described the conditions as "the first time in my experience in the Atlantic in 24 years, and I have been going across the Atlantic nearly all the time, of seeing an absolutely flat sea"(24.) and elaborated on the lack of wind and the effect on the sea and icebergs.

In the event of meeting ice there are many things we look for. In the first place a slight breeze. Of course, the stronger the breeze the more visible will the ice be, or rather the breakers on the ice. Therefore at any time when there is a slight breeze you will always see at nighttime a phosphorescent line round a berg, growler, or whatever it may be; the slight swell which we invariably look for in the North Atlantic causes the same effect, the break on the base of the berg, so showing a phosphorescent glow. All bergs - all ice more or less have a crystallised side… it has been crystallised through exposure and that in all cases will reflect a certain amount of light, what is termed ice-blink, and that ice-blink from a fairly large berg you will frequently see before the berg comes above the horizon… As far as we could see from the bridge the sea was comparatively smooth. Not that we expected it to be smooth, because looking from the ship’s bridge very frequently with quite a swell on the sea will appear just as smooth as a billiard table, perfectly smooth; you cannot detect the swell. The higher you are the more difficult it is to detect a slight swell. (British Inquiry(24.))

Lightoller also noted at the British Inquiry that "the conditions of an absolutely flat sea were not apparent to us till afterwards." Lightoller believes it is impossible to 'smell' ice in advance: “It is often said you can tell when you are approaching ice, by the drop in temperature. The answer to that is, open a refrigerator door when the outside temperature is down, and see how close you have to get before you detect a difference. No, you would have to be uncomfortably close to 'smell' ice that way.” (US Inquiry(25.))

Lightoller believes, according to his book, that the disaster was caused by wireless operator Jack Phillips not passing on an ice message from the Mesaba.

“When standing with others on the upturned boat, Phillips explained when I said that I did not recollect any Mesaba report: “I just put the message under a paper weight at my elbow, just until I squared up what I was doing before sending it to the Bridge.” That delay proved fatal and was the main contributory cause to the loss of that magnificent ship and hundreds of lives. Had I as Officer of the Watch, or the Captain, become aware of the peril lying so close ahead and not instantly slowed down or stopped, we should have been guilty of culpable and criminal negligence.”(47.)

However his recollection of Phillips on the upturned lifeboat in his book 24 years later is almost undoubtedly faulty, as his 1912 evidence and the testimony of fellow survivor Archibald Gracie indicates it was actually the surviving wireless operator, Harold Bride, that Lightoller was referring to, and so unfairly points the finger at Phillips. (For more information see the section on the writing of his book here, where Bride later criticises Lightoller).

He had first emphasised its importance at the British Inquiry, stating that "I think had that message been delivered, even to the Captain, he would immediately have brought the message out personally to the bridge; he would not even have sent it out, and he would have seen it was communicated to all the senior officers, as well as distinctly marked on the chart. It was of the utmost importance."(British Inquiry(24.))

Later, in his 1936 BBC broadcast, Lightoller was even more adamant about the importance of the Mesaba message:

When the evidence came to be sifted out at the Inquiry held in London afterwards it then came out that one very vital message received in the Titanic's wireless room that night had never been delivered to the bridge. That message came from a ship called the Mesaba warning all ships of heavy pack, ice icebergs and field ice in an area then lying right ahead of the Titanic and what was still worse, not far away.

Those immense quantities of ice were abnormal for almost any time of the year and the significance we should have attached to that report can hardly be exaggerated. In my opinion, it was a warning of the most vital importance. You see I was officer of the watch and in charge of the ship when that Mesaba message came over and I hope perfectly well what I should have done if it had come to my hands. Without a shadow of doubt, I should have slowed her down at once. That would have been imperative and sent for the captain. More than likely, in fact almost certainly, he would have stopped the ship altogether and waited for daylight to feel his way through. Anyhow the long and short of it is, neither, he nor I nor any other officer of the ship got that message. (BBC, 1936)

The 6833 ton SS Mesaba was built by Harland & Wolff, Ltd., Belfast in 1898 and owned by the Atlantic Transport Co. Ltd., Liverpool. (Click image to enlarge)

Iceberg Collision

At 11:40pm Titanic encounters an iceberg, a collision with which proves fatal. At the time he "had just switched the light out... and turned over to go to sleep…but I was still awake" (British Inquiry(24.)).

He describes the impact as " a slight shock, a slight trembling, and a grinding sound. She did not make any alteration in her course, so far as I am aware. " (US Inquiry(25.)). "It is best described as a jar and a grinding sound. There was a slight jar followed by this grinding sound. It struck me we had struck something and then thinking it over it was a feeling as if she may have hit something with her propellers, and on second thoughts I thought perhaps she had struck some obstruction with her propeller and stripped the blades off. There was a slight jar followed by the grinding - a slight bumping...(British Inquiry(24.))

He then "lay there for a few moments, it might have been a few minutes, and then feeling the engines had stopped I got up. ….I, first of all, looked forward to the bridge and everything seemed quiet there. I could see the First Officer standing on the footbridge keeping the look out. I then walked across to the side, and I saw the ship had slowed down, that is to say, was proceeding slowly through the water...All on the port side." (British Inquiry(24.))

According to his book Lightoller incorrectly states that “the time we struck was 12:00 p.m." He describes how he felt the collision:

"I was just about ready for the land of nod, when I felt a sudden vibrating jar run through the ship. Up to this moment she had been steaming with such a pronounced lack of vibration that this sudden break in the steady running was all the more noticeable. Not that it was by any means a violent concussion, but just a distinct and unpleasant break in the monotony of her motion. I instantly leapt out of my bunk and ran out on deck in my pyjamas; peered over the port side, but could see nothing there; ran across to the starboard side, but neither was there anything there, and as the cold was cutting like a knife, I hopped back into my bunk..."(47.)

Third officer Pitman, also 'undressed', had already been outside to see what happened and on seeing noone was returning to his cabin when he saw Lightoller. "He was off watch then; he was in bed" his quarters were "next door" and "I saw him when I was coming back; on my return." (US Inquiry). At the British Inquiry Pitman said he "met Mr. Lightoller first of all, and I asked him what had happened, if we had hit something, and he said, 'Yes, evidently.'' ...Yes, evidently something had happened." (25.)

At the British Inquiry Lightoller describes "after looking over the side and seeing the bridge I went back to the quarters and crossed over to the starboard side. I looked out of the starboard door and I could see the Commander standing on the bridge in just the same manner as I had seen Mr. Murdoch, just the outline; I could not see which was which in the dark. I did not go out on the deck again on the starboard side. It was pretty cold and I went back to my bunk and turned in."(25.)

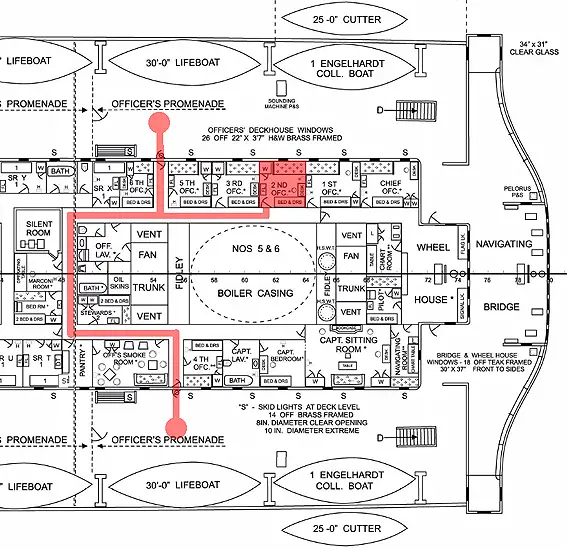

Titanic's boat deck with Lightoller cabin highlighted as well as the likely route he took to the port and starboard boat decks, where he "could see nothing" (deck plans: Encyclopedia Titanica)

Immediately after the collision, the watertight doors are closed by First Officer Murdoch, something Lightoller describes during the British Inquiry:

You communicate by the bell push, just an alarm bell, previously, and then put the handle over….You put the lever over to “on” on the bridge. That forms a contact alongside the watertight doors and releases a friction clutch which allows the door to descend. As long as the lever is over to “on” I understand the doors cannot be lifted; but if you put the lever to “off” the doors have then to be raised by hand and can be raised by hand. (British Inquiry(24.))

Fourth officer Boxhall knocks on Lightoller's

door and tells him of the iceberg collision.

Lightoller does not believe the ship was ever ordered "full astern" during the evasive maneouvre, notably saying that" I cannot say I remember feeling the engines going full speed astern." (British Inquiry)

Lightoller waited in his quarters - as an off-duty officer would be unwelcome on the bridge unless asked for. He explained during his 1936 BBC radio broadcast: "If I was wanted, naturally my cabin would be the first place where anyone sent for me would look. You see apart from being nearly frozen even an officer when on watch isn't exactly welcomed on the bridge either in pajamas or anything else. " (BBC, 1936)

Fourth Officer Boxhall was the one to finally break the news:

About ten minutes later that the Fourth Officer, Boxall (sic) opened my door, and , seeing me awake, quietly said, “We’ve hit an iceberg.” I replied, “I know you’ve hit something.” He then said, “The water is up to F Deck in the Mail Room.” That was quite sufficient. Not another word passed. He went out, closing the door, whilst I slipped into some clothes as quickly as possible, and went out on deck…. The fact of the water having reached “F” deck, showed me she had been badly holed, but, at the time, although I knew it was serious, I had not a thought that it was likely to prove fatal; that knowledge was to come much later.” (47.)

In his BBC broadcast he said: "I was into a pair of pants, sweater and bridge coat and out on deck almost as soon as he was." (BBC, 1936)

Opinion regarding the collision

In his 1936 BBC broadcast Lightoller says that he believes Murdoch saw the berg at the same time as the lookout men, but speed was a factor:

Murdoch evidently saw the mass of ice practically at the same time as the lookout men and shouted "Hard-a-starboard, full speed astern." His idea was to swing her bow clear and then put the helm hard over the other way and so swing her stern clear. And given half a chance, I'd believe he'd have done it, but going at that speed it was too late. As it was, our bow swung a bit, but not enough and she struck. She took the blow on her starboard side masses of ice actually falling on the foredeck. But what was worse, though we didn't know that till it came out of the inquiry, she was pierced below the waterline in no less than six compartments. And from that moment nothing could have saved her.(47.)

Lightoller also comments on the nature of the collision, that it was more of a grounding and due to Titanic's size more damage occurred. He writes in his book:

“She struck the berg well forward of the foremast, and evidently there had been a slight shelf protruding below the water. This pierced her bow as she threw her whole weight on the ice, some actually falling on her fore deck. The impact flung her bow off, but only by the whip or spring of the ship. Again she struck, this time a little further aft. Each blow stove in a plate, below the water line, as the ship had not the inherent strength to resist.

Had it been, for instance, the old Majestic or even the Oceanic the chances are that either of them would have been strong enough to take the blow and be bodily thrown off without serious damage. For instance, coming alongside with the old Majestic, it was no uncommon thing for her to hit a knuckle of the wharf a good healthy bump, but beyond, perhaps, scraping off the paint, no damage was ever done. The same, to a lesser extent with the Oceanic.

Then ships grew in size, out of all proportion to their strength, till one would see a modern liner brought will all the skill and care possible, fall slowly, and ever so gently on a knuckle, to bend and dent a plate like a piece of tin.

That is exactly what happened to the Titanic. She just bump, bump, bumped along the berg, holing herself each time, till she was making water in no less than six compartments, though, unfortunately, we were not to know this until much later.”(47.)

At the British Inquiry he suggests that in addition to the "extraordinary combination of circumstances" it could have been "black ice":

Of course, we know now the extraordinary combination of circumstances that existed at that time which you would not meet again once in 100 years; that they should all have existed just on that particular night shows, of course, that everything was against us…..In the first place, there was no moon….Then there was no wind, not the slightest breath of air. And most particular of all in my estimation is the fact, a most extraordinary circumstance, that there was not any swell. Had there been the slightest degree of swell I have no doubt that berg would have been seen in plenty of time to clear it. …..The berg into which we must have run in my estimation must have been a berg which had very shortly before capsized, and that would leave most of it above the water practically black ice. …..or it must have been a berg broken from a glacier with the blue side towards us, but even in that case, had it been a glacier there would still have been the white outline that Captain Smith spoke about, with a white outline against, no matter how dark a sky, providing the stars are out and distinctly visible, you ought to pick it out in quite sufficient time to clear it at any time. That is to say, providing the stars are out and providing it is not cloudy. …The only way in which I can account for it is that this was probably a berg which had overturned as they most frequently do, which had split and broken adrift; a berg will split into different divisions, into halves perhaps, and then it becomes top-heavy, and at the same time as it splits you have what are often spoken of as explosions and the berg will topple over. That brings most of the part that has been in the water above the water. (British Inquiry (24.))

Does Lightoller believe that speed was to blame? He was asked at the US Inquiry:

Senator FLETCHER. If the vessel had been running at a lower rate of speed would not the chances of avoiding that iceberg have been increased?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. When a vessel is running at a low rate of speed, she is slower on the helm so the conditions would be totally different... which means that she would take longer to swing on her helm in proportion to her reduced speed.

Senator FLETCHER. She would have had more time in which to swing, would she not?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. She would have had more time in which to swing.(25.)

Tellingly, at the British Inquiry, he sadly notes that if he had been the Officer of the Watch on duty at the time "I do not pretend to have been able to see it any further than my brother officer, Mr. Murdoch." (British Inquiry(24.))

If this website has been of some help, please consider supporting it with a coffee

to ensure it can continue. It can be anonymous. Anything helps!: