Side Menu:

Second Officer C.H.Lightoller

- Rescue Aboard Carpathia and the US Inquiry

The Cunard Liner, the RMS Carpathia under Captain Arthur Rostron, had been steaming at full speed for Titanic's last distress position, arriving at 4am. For the next four and a half hours, the ship collected survivors from the lifeboats, with the overloaded lifeboat 12, with about 60 people, with Lightoller in command the last to reach the rescue ship. Its gunwales were only three inches above the water line. Lightoller describes the process in his book:

As daylight increased we had the thrice welcome sight of the Cunard Liner Carpathia cautiously picking her way through the ice towards us. We saw boat by boat go alongside, but the question was, would she come our way in time? Sea and wind were rising. Every wave threatened to come over the bows of our overloaded lifeboat and swamp us. All were women and children in the boat apart from those of us men from the Engleheart (sic). Fortunately, none of them realised how near we were to being swamped.

I trimmed the boat down a little more by the stern, and raised the bow, keeping her carefully bow on to the sea, and hoping against hope she would continue to rise. Sluggishly, she lifted her bows, but there was no life in her with all that number on board.

Then, at long last, the Carpathia definitely turned her head towards us, rounding to about 100 yards to windward. Now to get her safely alongside! We couldn’t last many minutes longer, and round the Carpathia’s bows was a scurry of wind and waves that looked like defeating my efforts after all. One sea lapped over the bow, and the next one far worse. The following one she rode, and then, to my unbounded relief, she came through the scurry into calm water under the Carpathia’s lee.

Quickly the bosun’s chairs were lowered for those unable to climb the sheer side by a swinging rope ladder, and little enough ceremony was shown in bundling old and young, fat and thin, onto that bit of wood constituting the “Boatswain’s Chair.” Once the word was given to “hoist away” and up into the air they went. There were a few screams, but on the whole, they took it well, in fact many were by now in a condition that rendered them barely able to hang on, much less scream.”(47.)

Lifeboat 12 was the last lifeboat taken aboard the Carpathia, at about 8:30am, and Second officer Lightoller deliberately held back, waiting to be the last person to climb aboard the rescue ship. He first met with Captain Roston and then changed:

I was the last member of the Titanic to board the Carpathia, and after interviewing her Captain, discarded my wet clothes in favour of a bunk, in which remained for about half an hour, and was not in bunk or bed again till we arrived in New York. Reaction or effects from the immersion - which I was confidently assured would take place - there were none; and though surprise had been expressed by very many, it only goes to prove that 'with God all things are possible.' (Christian Science Sentinel, October 1912)

Lightoller (middle) talks with Captain Arthur Rostron (right) on board R.M.S. Carpathia looked on by the ship's Chief Officer Hankinson

Onboard the Carpthia, Lightoller was involved in counting the survivors and also checking the lifeboats. In his autobiography he wrote:

"When all were on board, we counted the cost. There were a round total of 711 saved out of 2,201 on board. Fifteen hundred of all ranks and classes had gone to their last account. Apart from four junior officers (sic) ordered away in charge of boats, I found I was the solitary survivor of over fifty officers and engineers who went down with her. Hardly one amongst the hundreds of surviving passengers, but had lost someone near and dear.”(47.)

Lightoller's number of 711 is very close to the actual number of survivors now established as 712. Second class passenger Lawrence Beesley wrote in his book, The Loss of the SS Titanic, about checking the lifeboats with Third officer Pitman:

I have a letter from Second Officer Lightoller in which he assures me that he and Fourth Officer Pitman examined every lifeboat from the Titanic as they lay on the Carpathia's deck afterwards and found biscuits and water in each. Not that we wanted any food or water then: we thought of the time that might elapse before the Olympic picked us up in the afternoon.

At the British Inquiry Lightoller gave a few more details about the lifeboat checks:

14861. After you were taken on the “Carpathia,” did you yourself go round the boats belonging to the “Titanic”? - I did…There were 13 saved - 11 lifeboats and two emergency boats... I also found several lamps hanging in the thwarts when we were on board the “Carpathia” which evidently had not been used… Lamps belonging to the “Titanic’s” lifeboats." (British Inquiry(24.))

Lightoller also spoke with passengers, including Colonel Archibald Gracie and exchanged contact details. At the US Inquiry Lightoller said "I think I have his card."(25.)

Lightoller also spent time with White Star Line president, Bruce Ismay, who, according to his US Inquiry testimony, Bruce Ismay consulted with Lightoller after the disaster and is the only officer known to him of the four surviving officers.

Escape on the Cedric

Lightoller as pictured in the 18th of April 1912

Daily Mirror.

After the lifeboats had been recovered, Captain Rostron made the decision to sail for New York, rather than Halifax, Titanic's intended destination. Already Lightoller was looking at options so as to avoid an inquiry, and wrote in his autobiography:

“Everybody’s hope, so far as the crew were concerned was that we might arrive in New York in time to catch the Celtic (sic) back to Liverpool and so escape the inquisition that would otherwise be awaiting us. Our luck was distinctly out. We were served with Warrants, immediately on arrival.(47.)

Later at the US Inquiry he had to clarify exactly what had happened, as Ismay's behaviour was coming under question in regards to the Cedric and what appeared to be an effort to suppress the facts of the disaster. Lightoller attempted to take the blame by offering the Senator an voluntary statement:

We were saying all the time, "It is a great pity if we will miss the Cedric. If we could only get home in time to get everybody on board the Cedric, we shall probably be able to keep the men together as much as possible." Otherwise, you understand, once the men get in New York, naturally these men are not going to hang around New York or hang around anywhere else. They want to get to sea to earn money to keep their wives and families, and they would ship off. You can not find a sailor but what will ship off at once if he gets the opportunity... Our crew would in all probability have done the same, and we would have lost a number of them, probably some very important witnesses...

A telegram was dispatched asking them to hold the Cedric until we got in, to which we received the reply that it was not advisable to hold the Cedric. He asked what I thought about it. I said, "I think we ought to hold her, and you ought to telegraph and insist on their holding her and preventing the crew getting around in New York." We discussed the pros and cons and deemed it advisable to keep the crew together as much as we could, so we could get home, and we might then be able to choose our important witnesses and let the remainder go to sea and earn money for themselves. So I believe the other telegram was sent.

I may say that at that time Mr. Ismay did not seem to me to be in a mental condition to finally decide anything. I tried my utmost to rouse Mr. Ismay, for he was obsessed with the idea, and kept repeating, that he ought to have gone down with the ship because he found that women had gone down.(25.)

It must have seemed obvious to the Senator that the issue was a sensitive one as later Senator Smith picked up on his statement:

Senator SMITH. You made a statement a few minutes ago about Mr. Ismay which evidently was a voluntary statement. No one asked you about it. Why did you not make that statement in New York?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. Because the controversy in regard to the telegram had not been brought up then, or brought to my knowledge; I mean all this paper talk there has been about this telegram...

Senator SMITH. Did you know at that time that an inquiry had been ordered by the Senate?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. Certainly not or we should never have dreamed of sending the telegram. Our whole and sole idea was to keep the crew together for the inquiry, presumably at home. We naturally did not want any witnesses to get astray.

Senator SMITH. Did you know when the Cedric was to sail?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. Yes, Thursday morning. I think I even suggested, if they would not hold her at the dock, to exchange at Quarantine.

Senator SMITH. You made that suggestion?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. I did.

Senator SMITH. To whom?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. To Mr. Ismay. Our whole idea was to get them on board the Cedric.

Senator BOURNE. Your idea was to keep them together, take care of them, and furnish them transportation back to their homes, was it not?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. Back to where the inquiry would be; and, naturally human nature will try to get the men back to their wives and families as soon as possible. Their income stops, you know, from the time the wreck occurs, legally.

New York and the United States Inquiry

The Carpathia docked on the evening of 18 April 1912 and upon arrival the surviving officers and crew, and also Bruce Ismay were served with subpoenas.

Lightoller immediately ordered clothing for the crew. In a Marconigram dated 18th April 1912 to: Saks & Co., New York. ''36 men's medium flannel shirts 12 men's ditto, drawers, 12 pairs socks for destitute, deliver immediately at Pier 54 to Officer C. H. Lightoller. Lelia.'' And also on the same date: "Siegel Cooper & Co. 6th Avenue, New York. ''25 Coats, 19 Trousers medium weight for destitute deliver immediately at pier 54 to Officer C. H. Lightoller. - Julia''.

Lightoller's wife, Sylvia, in Southampton, received more than fifty telegrams congratulating her that the Second Officer had survived, and another batch of fifty telegrams expressing condolences based on the news that the First Officer had died. Only when her husband’s telegram came through from New York could her mind be truly set to rest. According to the Chorley Guardian of July 18, 1958, Sylvia heard the news in the following manner:

"The casualties and survivors were announced with ranks only - without names", she said. "''"I received 50 telegrams congratulating me because the second officer had survived and 50 telegrams of condolence because the first officer had been lost. The disaster occurred on a Sunday and it was not until the Friday that my husband's cable from New York reached me saying that 'he was safe'." Chorley Guardian of July 18, 1958.

In a Saturday 20th of April 1912 newspaper it reported:

Mrs. Lightoller, who has two little boys, had just returned from Southampton, where she had been visiting the wives of other officers less fortunate than herself, and said how terribly anxious she had been, but how thankful she felt now that she was assured of her husband's safety.

Mr. Lightoller, who comes from Liverpool, has seen service with the White Star line on the liners Teutonic and Oceanic, but recently has been engaged on the Majestic. Mrs. Lightoller is a native of Australia, and, with her husband, have been living at Netley since the Company came to Southampton. Mrs. Lightoller said that she had endeavoured to see the Mayor of Southampton, to ask what she might do to help in collecting at Netley, as she thought she ought to do everything in her power now she herself was relieved from anxiety. In conclusion, Mrs. Lightoller said she had been besieged with telegrams of inquiry and congratulations, and wished to thank those who had sent, for she could not possibly reply to so many.(Southampton Times and Hampshire Express

Saturday 20th April 1912)

An artist's sketch of Lightoller testifying

before the Senate Committee

Wasting no time, the hearings began in New York on April 19, 1912, at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, New York, the day after the Carpathia had arrived, then later moved to Washington, D.C., concluding on May 25, 1912 with a return visit to New York, taking a total of 18 days. The eight Senators involved in the questioning were not nautical authorities, and Lightoller was annoyed by their lack of expertise. He described the US Inquiry in his book as "a colossal piece of impertinence that served no useful purpose and elicited only a garbled and disjointed account of the disaster; due in the main to a total lack of co-ordination in the questioning with an abysmal ignorance of the sea.”(47.)

When the Inquiry was moved to Washington, they were provided with allegedly unsuitable accommodation:

"In Washington our men were herded into a second-rate boarding house, which might have suited some, but certainly not such men as formed the crew of the Titanic. In the end they point blank refused to have anything more to do with either the enquiry or the people, whose only achievement was to make our Seamen, Quartermasters and Petty Officers look utterly ridiculous. It was only with the greatest difficulty I was able to bring peace into the camp—mainly due to the tact exhibited by the British Ambassador, Lord Percy, and Mr. P.A. Franklyn (sic), President of the International Mercantile Marine Co.”(47.)

Also, in his autobiography he went on to write: “With all the goodwill in the world, the ‘enquiry’ could be called nothing but a complete farce, wherein all the traditions and customs of the sea were continuously and persistently flouted.”(47.)

However, as a witness Lightoller was not always helpful and was sometimes even contradictory in his statements. He mentions being at many of the port side boats, but does not specify which, other than by 'first boat, second boat' which has caused much confusion as to lifeboat numbers and timings over the years.

When describing how he left the ship, he replied that it 'left him' which is not entirely true, as we know Lightoller walked or most likely dove from the roof of the officer's quarters, as in 1936 he described the moment as when he "hoved into the water". But more concerningly, he stated under oath that he did not discuss ice when passing the final watch to First officer Murdoch, an error that had to be rectified during the British Inquiry.

In other examples, he admits to his memory not being clear and forgetting key points of interest and tries to avoid repeating himself for fear of contradiction. For example, when asked about talking to Ismay:

Senator SMITH. How long was that after the collision?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. I think you will find that in the testimony.

Senator SMITH. I know I will find it there, but I want it again. Your recollection is just a little better to-day than it was the other day, and I would like to test it out a little.

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. My mind was fresher on it then, perhaps, than it is now.(25.)

And even in a short space of time admits to forgetting:

Senator SMITH. How many seamen were there in that boat, and what was the number of it, if you know?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. No. 6, I believe.

Senator SMITH. How many people did it contain when you got ready to lower it into the water?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. I think I have given all that in my testimony.

Senator SMITH. I know; but I have forgotten it.

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. Well, I have forgotten it, too.

Senator SMITH. And you do not care to make any statement about it?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. No, sir; I do not.(25.)

He was also very obviously protecting his employers, especially in regard to Bruce Ismay. For example he made the following statement, likely in response to newspaper reports, as to Ismay's departure:

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. Chief Officer Wilde was at the starboard collapsible boat in which Mr. Ismay went away, and that he told Mr. Ismay, "There are no more women on board the ship." Wilde was a pretty big, powerful chap, and he was a man that would not argue very long. Mr. Ismay was right there. Naturally he was there close to the boat, because he was working at the boats and he had been working at the collapsible boat, and that is why he was there, and Mr. Wilde, who was near him, simply bundled him into the boat.

Senator SMITH. You did not say that before?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. No; but I believe it is true, I forget the source. I am sorry I have forgotten it.(25.)

Lightoller was also suspiciously illusive when it came to the ice reports. Dr Paul Lee in his Titanic website, which details all of the ice warnings, summarises his statements:

With the commencement of the US Inquiry, Lightoller was asked if he knew they were in the vicinity of icebergs. With all we have learned above, Lightoller issued an astonishing "no." He must have been surprised to be asked next about the "Amerika" ice warning - which had been relayed to Washington by his ship, no less! Admitting that he "could not say" if he had heard of it, he then admitted that he had received an ice message (this was from the "Caronia"), and then via torturous, repetitive questioning, he said that they expected to be in ice about 11 o'clock. Aside from this one warning, he claimed that he had no reason to believe that they were in the vicinity of ice. This doesn't jibe at all with his later comments.(Dr Paul Lee, http://paullee.com/titanic/icewarnings.php)

In the end, the US Inquiry report concluded that Captain Smith was to blame having shown an "indifference to danger [that] was one of the direct and contributing causes of this unnecessary tragedy." and the lack of lifeboats was the fault of the British Board of Trade, "to whose laxity of regulation and hasty inspection the world is largely indebted for this awful tragedy."(25.)

At midday Thursday May the 2nd, 1912, Lightoller, along with the three other surviving officers, thirty crew members, and White Star President Bruce Ismay, were able to depart for England, boarding the Adriatic from New York City. They arrived in Liverpool, UK on 11 May, 1912.

Lightoller was fortunate to make the Adriatic - he, along with Ismay and Boxhall, had been served with subpoenas by the District Supreme Court to give evidence on an affidavit by a Mrs Louise Roberts, the wife of John Jacob Astor’s valet, who was preparing a suit for damages against the White Star Line. When threatened with legal action for departing DC to go to NY, it was argued that he could not be subpoenaed again within 24 hours of the US Congressional Inquiry having released him. Legal representatives of the three men reached an agreement with the attorneys of Mrs Roberts that the men would return to America the following Autumn to give their testimony when the case came up.

Lightoller's Letters

During his time at the United States Inquiry, Lightoller wrote a letter to Ada Murdoch in Southampton, the widow of First officer Murdoch, dated April 24th, 1912 and co-signed by the three other surviving officers, Boxhall, Pitman and Lowe, "to refute the reports that were spread in the newspapers. I was practically the last man, and certainly the last officer, to see Mr. Murdoch….Other reports as to the ending are absolutely false. Mr. Murdoch died like a man, doing his duty."

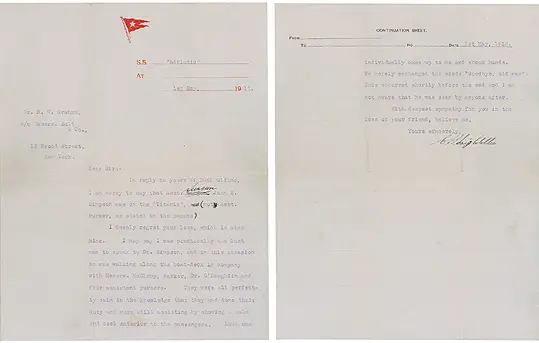

Later on May the 1st, the day before departing the States, Lightoller wrote a letter to a Mr R.W. Graham, on White Star Line letterhead aboard the RMS Adriatic, stating "I may say I was practically the last man to speak to Dr Simpson... We merely exchanged the words "Goodbye, old man".This occurred shortly before the end and I am not aware that he was seen by anyone after. With deepest sympathy for you in the loss of your friend."

It is not known how many letters Lightoller wrote of this nature to the family of lost crew members.

Lightoller's letter to a Mr R.W. Graham, on White Star Line letterhead aboard the RMS Adriatic. (Click image to enlarge)

If this website has been of some help, please consider supporting it with a coffee

to ensure it can continue. It can be anonymous. Anything helps!: