Captain Herbert Haddock

- Titanic & Olympic

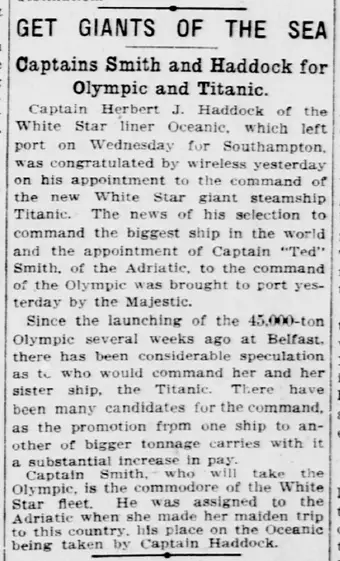

As early as 1910 Haddock was destined to command the Titanic - if an early newspaper report is to be believed:

GET GIANTS OF THE SEA |

In 1911, speculation as to Titanic's captain lead The New York Times to write that "the Titanic, which is to enter the New York-Southampton service toward the end of the year, will be commanded, it is said, either by Capt. B. H. Hayes of the Adriatic or Capt. Henry Smith." (June 6 1911, The New York Times)

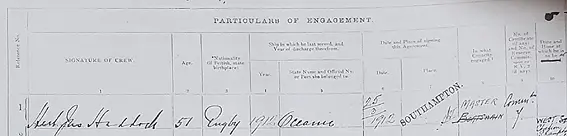

On the 25th of March 1912, 51-year old Herbert Haddock, after serving aboard the Oceanic for four years, was transferred to a ship in Belfast being prepared for her sea trials, the now legendary RMS Titanic, supervising until Captain Edward Smith completed one more Olympic voyage.

Titanic's "Particulars of Engagement in Belfast" show that he signed the document in Southampton on the 25th and then travelled to Belfast to take command. Included in the document are officers Lightoller and Blair, as first and second officers respectively, that he would have known from their time aboard the Oceanic.

Titanic's Particulars of Engagement in Belfast lists Haddock as "Master".

(Image: Public Record Office/Nicola Foster)

(Click image to enlarge)

The senior officers - Chief Officer William Murdoch, First Officer Lightoller and Second Officer David Blair arrived ahead of the junior officers - Third Officer Herbert Pitman, Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall, Fifth Officer Harold Lowe and Sixth Officer James Moody, who arrived at noon on the 27th of March.

One of the junior officers who knew Haddock was James Moody, who included a reference to him in a letter he wrote. Of his new captain, Edward "E.J." Smith, Moody observed, "Though I believe he's an awful stickler for discipline, he's popular with everybody". He then references Captain Haddock of the Olympic- "Daddy Haddock' is going to the Olympic until old 'E.J.' retires on his old age pension from the Titanic..." (Bridge Duty, Officers of the RMS Titanic, Inger Sheil & Kerri Sundberg 1999)

Haddock's job was to prepare the ship for her sea trials scheduled to take place on the 1st of April, the date when Edward Smith arrived to take over from Haddock as master for the trials, delivery trip and maiden voyage.

It must have been an impressive ship for Haddock. Titanic was 200 feet longer and 28,000 tons heavier than the Oceanic. His colleague from Oceanic, Lightoller was very impressed with the size and wrote it "is difficult to convey any idea of the size of a ship like the Titanic, when you could actually walk miles along decks and passages, covering different ground all the time... it took me fourteen days before I could with confidence find my way from one part of that ship to another by the shortest route." ("Titanic and Other Ships," Charles Herbert Lightoller)

During that week leading up to the sea trials Haddock supervised the Board of Trade inspection, during which Titanic's anchors, lifeboats and other safety equipment were inspected.

"On Friday, March 29, Haddock continued to oversee the mustering of Titanic's crew as seventy-nine firemen and stokers signed on to the new ship for her upcoming sea trials and subsequent voyage to Southampton. The notoriously publicity-shy captain was no doubt less enthusiastic about another duty that day - to welcome a special party, comprising mostly journalists, who were invited aboard to inspect the new Titanic before she departed Belfast. On Sunday, March 31, Haddock got a chance - albeit it a short lived one - to experience the power of the Olympic class for himself when he swung Titanic around to face the sea on the eve of her sea trials."

(Racing Through the Night, Wade Sisson)

However Sisson's reference to swinging the Titanic around to face the channel in preparation for her sea trials is unlikely. According to Titanic in Photographs by Daniel Klistorner and Steve Hall, on the 8th of March the Titanic was taken out of dry dock and placed back at the fitting wharf with her bow facing the channel. "Owing to difficulties with manoeuvering Olympic in the strong winds, as a precaution, Titanic was turned at this time so her bow faced the channel. This would make a later turning unnecessary and she could depart as soon as she was ready several weeks hence." (Titanic in Photographs by Daniel Klistorner and Steve Hall)

Although he was in command of Titanic for only 6 days - from March 25th, to March 31st, 1912, he is officially Titanic's first master and commander. But his story does not end there, as he also played an important role during and after the sinking.

RMS Olympic

The few days he spent as Titanic's first captain were good preparation for his next assignment, as he immediately returned to Southampton to take command of Smith's previous ship, RMS Olympic. According to Wade Sisson, the Olympic had a "compliment of crew that was largely unfamiliar with the grand size and scale of a large ship."

On the 3rd of April 1912 the Olympic began its tenth Southampton to New York round trip, arriving in New York on the 10th of April, the day Titanic left Southampton.

The RMS Olympic, under the command of Captain Haddock, arrived in New York on the 10th of April 1912 - the day Titanic departed Southampton. (Click image to enlarge)

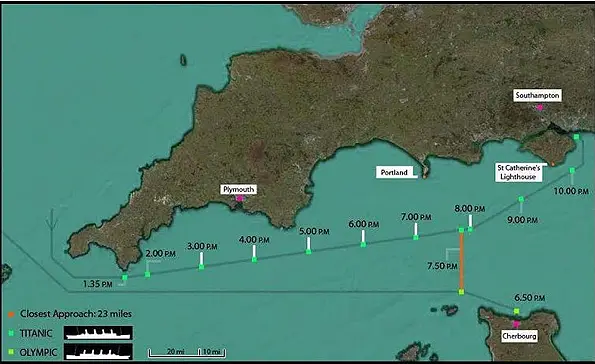

When the Olympic departed from Cherbourg on April 3rd, it has been wondered whether it passed Titanic on her delivery trip to Southampton. Maritime artist Ken Marschall even painted a fantastic recreation of the two ships passing each other, as the Titanic had swerved from her original course to pass by within sight of each other, possibly allowing Smith and Haddock to wave a friendly hallo.

A painting by maritime artist Ken Marschall showing the Titanic and Olympic passing each other. (Click image to enlarge)

However, thanks to the research of Dr Paul Lee, Ioannis Georgiou and Steve Hall, the exact proximity of the two ships has been calculated at being no closer than 23 miles during the evening of the 3rd of April, complicated by the fact that it was approaching nautical twilight, although "it is possible that the very faint glimmerings of each other's mastlights could be seen from the crows nest." (Please refer to "The Delivery Trip : Miscellaneous Titanic Navigation Notes" by Paul Lee: http://www.paullee.com/titanic/tnav.php)

A diagram by Dr Paul Lee showing the Olympic and Titanic's closest approach of 23 miles.

(Click image to enlarge)

Titanic Disaster

That was certainly not the end of Haddock's connection with Titanic. On the 13th of April 1912, the Olympic departed New York at 3pm under Haddock's command, on her journey eastward towards England, on her return to Southampton. The two ships were about to pass each other again, mid-Atlantic, until late at night on April 14th, the Olympic received the first of many distress calls from Titanic, having struck an iceberg.

According to Captain Haddock, when later questioned during the Senate Inquiry "roughly, we were west by south 500 miles of the Titanic" at "New York time, 10.50 p. m., Sunday."(US Inquiry) This measurement is 500 nautical miles (930 km; 580 mi) west by south of Titanic's location

The two Olympic wireless operators who received

a distress call from the 'Titanic' in April 1912. They

are First Wireless Operator Ernest James Moore

(left) and Junior Wireless Operator Alec Bagot.

(Photo by Paul Thompson/FPG/Getty Images).

(Click to enlarge)

First Wireless Operator Ernest James Moore took the distress calls and kept a report of the messages. Moore wrote:"Hear Titanic signaling to some ship about striking an iceberg. Am not sure if it is the Titanic who has struck an iceberg. Am interfered by atmospherics and many stations working."

Ten minutes later, according to Haddock, they heard a direct C.Q.D call from Titanic and Moore "answered his calls immediately." Haddock reported to the Senate: "It was 10 minutes later after I got the first call from her, and then worked out the course and distance to where she was, altered course toward her, and at the same time sent for chief engineer to get up full power." (US Inquiry)

According to Wade Sisson's book "Racing Through the Night: Olympic's Attempt to Reach Titanic" even though the Olympic was the most distant ship to hear Titanic's distress message, Haddock managed to increase the Olympics' speed from 19 knots to 23, possibly 24 knots. "As Olympic's passengers slept, the ship's crew continued to prepare for the rescue operation that would transfer passengers and crew from the Titanic. The work was done as quietly as possible. Captain Haddock made it clear he didn't want word of Titanic's accident spreading beyond those who needed to know. " (Racing Through the Night, Wade Sisson)

From this point on, Haddock remained in constant contact with Titanic by wireless. The only surviving Titanic wireless operator, Harold Bride, later told the British Inquiry: "From the time we first established communication, Captain Haddock was sending us communications until the time we left the cabin for good." (British Inquiry)

Moore reported the following communications:

11.10 Titanic replies and gives me his position. 41.46 N. 50.14 W., and says: "we have struck an iceberg." Reported this information to bridge immediately. Our distance from the Titanic, 505 miles.

11.20 p. m. signals with the Titanic. He says: "Tell captain get your boats ready and what is your position?"

11.35 p. m. sent message to Titanic: "Commander Titanic, 4.24 a. m. GMT, 40.52 N. 61.18 W. Are you steering southly to meet us?- Haddock."

11.40 p. m., Titanic says, "Tell captain we are putting the passengers off in small boats."

11.45 p. m., Asked Titanic what weather he had had. He says, "Clear and calm."

11.50 p. m., Message to Titanic: "Commander Titanic, am lighting up all possible boilers as fast as can. - Haddock."

In response to the 11.20pm message "tell captain get your boats ready" Haddock responded by having all 16 of Olympic's lifeboats swung out on their davits.

Alec Bagot, the junior wireless operator on the Olympic, recalled in his book "Roaming Around" Haddock's response:

I sped along the port passage way leading from the wireless room, past the deck officers’ cabins, through the chart house to the bridge. Here were assembled with Captain Herbert Haddock, the First Officer, R. Hume; Second Officer, A. H. Fry, and two junior officers… Captain Haddock tore open the envelope, even in direst urgency Ernie Moore could never so far forget himself as to leave a radiogram unsealed.

‘I’ll answer it myself. Please come with me.’ I followed him into the chart room. On a message pad he wrote, ‘Commander Titanic Am lighting up all possible boilers as fast as I can – Haddock.’ Handing me the message, the Captain said: ‘Please send that urgent….Please ask your senior…. Mr. Moore, to stand by all the time and let me know immediately he gets any further news… ‘There is no need, of course, to say no mention of this business may be made outside.’ (""Roaming Around" by Alec Bagot)

Philip Albright Small Franklin, Vice

President of the United States of the

International Mercantile Marine

(Photograph: Paul Thompson)

Meanwhile, in New York, Philip Franklin, Vice President in the United States of the International Mercantile Marine Co. became aware that something was amiss with Titanic from the press at around 2am and "got Mr. Ridgway, the head of our steamship department, who lived in Brooklyn, and I asked him to at once go out and send a Marconigram to the captain of the Olympic. I did not want to alarm the captain of the Olympic. So all I asked in that telegram was, "Can you get the position of the Titanic? Wire us immediately her position." This was "sent at 3 A.M." (US Inquiry)

At 5.20am on Monday the 15th, Haddock received a message from the White Star Line in New York: "Capt. HADDOCK, Olympic: Endeavor communicate Titanic and ascertain time and position, reply as soon as possible to Ismay, New York. F. W. REDWAY." Followed by another at 7.35am "NEW YORK. COMMANDER Olympic: Keep us posted full regarding Titanic. FRANKLIN."

Junior Wireless operator Bagot remembered that these messages told them "that the New York Office was aware some thing had happened, but like ourselves, lacked details." ("Roaming Around" by Alec Bagot)

then replied at 7.45am "To ISMAY, New York: Since midnight when her position was 41.46 north 50.14 west have been unable to communicate, we are now 310 miles from her, 9 a. m., under full power, will inform you at once if hear anything. COMMANDER."

According to Franklin, who had no information at all regarding Titanic's status, he then replied to Haddock: "Can you ascertain damage Titanic?"

The second message from Haddock, received about 1pm, to Franklin then read: "Parisian reports Carpathia in attendance and picked up 20 boats of passengers and Baltic returning to give assistance. Position not given... Signed by Haddock." (US Inquiry)Franklin then replied to Haddock, about 2pm: "We have received nothing from Titanic, but rumored here that she proceeding slowly Halifax, but we can not confirm this. We expect Virginian alongside Titanic; try and communicate her."

Along with White Star, the press were also aware something had happened. Early Monday morning newspapers began to run headlines with conflicting reports about the Titanic - some even reporting "all saved." So it is no surprise that at 1.40pm on Monday the Olympic received a message that read: " CAPE RACE AND NEW YORK. WIRELESS OPERATOR, Olympic: We will pay you liberally for story of rescue of Titanic passengers."

Moore "then informed the operator that it was no use sending me messages from newspapers asking us to send news of the Titanic, as we had no news to give." This was one of several messages Moore received "to the same effect" from newspapers including the "New York Herald, the Sun, and the World." However Moore "did not send to any of them. I just made a note of that message just to show what we were receiving from time to time." (British Inquiry)

Bagot also recalls: "Another, more specific, offered thirty pounds a column, whilst others, open handed, said, ‘Name your own price.’ It was tempting, but time wasting. Even had we been inclined, we could not have broken our pledge to secrecy." ("Roaming Around" by Alec Bagot)

Carpathia's wireless operator

Harold Cottam: "I can not

do everything at once.

Patience, please."

Still unaware of what had happened, at 2pm Moore asked for news of the Titanic and received a reply from the Carpathia's wireless operator Harold Cottam "I can not do everything at once. Patience, please."

It must have been particularly frustrating for Haddock:

Captain Haddock was put in a particularly difficult position. His ship had the closest bond to Titanic and the most powerful wireless set on the Atlantic. If anyone had the capability to get the full story, it should have been him. Yet after 13 hours spent racing through the night, sending inquiries by wireless all the while, Haddock had more questions than answers. " (Racing Through the Night, Wade Sisson)

It was not until 4pm Monday, when the Olympic was about 100 nautical miles (190 km; 120 mi) from the Titanic's position, that the situation was finally made clear when Haddock received a message from Captain Rostron of the Carpathia:

"Fear absolutely no hope searching Titanic's position. Left Leyland S. S. Californian searching around. All boats accounted for. About 675 souls saved, crew and passengers, latter nearly all women and children. Titanic foundered about 2.20 a. m., 5.47. GMT in 41.16 north. 50.14 west; not certain of having got through. Please forward to White Star - also to Cunard. Liverpool and New York - that I am returning to New York. Consider this most advisable for many considerations. ROSTRON"

When Haddock was later questioned about the seeming delay in discovering what had happened, he explained: " I do not think that anybody failed to give us the information. The Carpathia had at that time a terrible job on her hands." (US Inquiry)

Later Moore "informed the Carpathia that if he had any important traffic to get through I would take it for him as I was then in communication with Cape Race.""HADDOCK." It was then Haddock's duty to pass on the terrible news to New York and the world at large. Moore noted that at "4.15 p. m., Told Carpathia that we would report the information to White Star immediately. 4.35 p. m., following service messages sent to Cape Race:"

"Olympic."

ISMAY, New York and Liverpool:

Carpathia reached Titanic position at daybreak; found boats and wreckage only. Titanic had foundered about 2.20 a. m. in 41.46 north 50.14 west; all her boats accounted for; about 675 souls saved, crew and passengers; latter nearly all women and children: Leyland Line S. S. Californian remaining and searching position of disaster; Carpathia returning to New York with survivors. Please inform Cunard.

"HADDOCK."

Haddock then followed it up with his own personal message to Franklin's office in New York, referencing the company code name for Bruce Ismay, YAMSI:

"Inexpressible sorrow. Am proceeding straight on voyage. Carpathia informs me no hope in seaching. Will send names survivors as obtainable. Yamsi on Carpathia. HADDOCK"

Haddock then sent a further message to the Carpathia at 4.50 p. m: "CAPTAIN Carpathia: Can you give me names survivors; forward? HADDOCK" An hour later Haddock received a reply, labelled "private" at 5.45pm:

"Private to Capt. Haddock. Olympic Captain, chief, first, and sixth officers, and all engineers gone. Also doctor, all pursers, one Marconi operator, and chief steward gone. We have second, third, fourth, and fifth officers and one Marconi operator on board."

This must have been a shock for Haddock -he personally knew Smith, Murdoch and McElroy. Moore and Haddock then received a series of message with the names of survivors including 322 first and second class passengers sent at 7.35pm.

Haddock then sent the following message: "Captain Carpathia, 7.12 p. m. G. M.T. Our position 41.17 north 53.53 west steering east true; shall I meet you and where? HADDOCK." Rostron replied "CAPTAIN Olympic: Do you think it advisable Titanic's passengers see Olympic? Personally I say not.ROSTRON. Carpathia." Before Haddock could reply Rostron then added: "CAPTAIN Olympic: Mr. Ismay's orders Olympic not to be seen by Carpathia. No transfer to take place. ROSTRON." Evidently, Rostron and Bruce Ismay had realised that the sight of the Olympic appearing would alarm and disturb the Titanic survivors, considering how similar the two ships were.

Bruce Ismay on his return to England.

During the British Inquiry, Bruce Ismay described the moment:

Captain Rostron came into my room on board the “Carpathia” and told me he had received a Marconigram from Captain Haddock that the “Olympic” was coming to us as quickly as possible. He suggested that it was very undesirable that our passengers on board the “Carpathia,” who were just settling down, should see the “Olympic,” as it would only probably harrow their feelings; the “Olympic” coming to us could do no good whatever, and I therefore entirely agreed with his suggestion that it was undesirable the ship should come to us.

Haddock agreed with Ismay and Rostron's instruction and replied:

"CAPTAIN Carpathia:

"Kindly inform me if there is the slightest hope of searching Titanic position at daybreak. Agree with you on not meeting; will stand on present course until you have passed and will then haul more to southward. Does the parallel of 41.17 north lead clear of the ice? Have you communicated the disaster to our people at New York or Liverpool? Or shall I do so and what particulars can you give me to send sincere thanks for what you have done?

After sending the list of survivors to Cape Race, at 2.30am on Tuesday the 16th of April, the Olympic then had the onerous task of passing on "service messages" to Cunard and the Associated press from Captain Rostron: "Carpathia. Cunard New York and Liverpool: Titanic struck iceberg Monday. 3 a. m., 41.16 north,. 50.14 west. Carpathia picked up many passengers in boats. Will wire further particulars later. Proceeding back to New York. ROSTRON"

Haddock was also involved in clarifying information, including:

S. S. Celtic, VIA CAPE RACE, N. F., April 16, 1912. ISMAY, New York: Please allay rumor that Virginian has any Titanic's passengers; neither has the Tunisian; believe only survivors on Carpathia; second, third, fourth, and fifth officers, and second Marconi operator only officers reported saved. 1.45 a. m. HADDOCK, Olympic.

The Olympics' wireless operators worked hard as a "clearing room" of messages across the Atlantic. Junior wireless operator Bagot remembers that they "were taking turn and turn about; both on watch or waiting on the Commander. Thoughtfully, Captain Haddock ordered an able seaman to ‘be in attendance during those fateful hours. He took up station just inside the door. " (Roaming Around by Alec Bagot)

It was also Haddock's responsibility to let the crew and passengers aboard the Olympic know the truth -as far as he had acertained. Crew and passengers were already aware from breakfast time that something was happening - all 16 lifeboats had been readied for lowering. According to Olympic passenger Madame Simone they discovered the news when a notice was posted up that the course toward Europe had resumed and that the Titanic had sank. Perhaps Haddock also had to consider the impact of the news on the passengers:

Haddock was filtering those few details that did come through in order to avoid a panic on board. After all, this was nearly the identical sister ship to a vessel that had just sunk with an appalling loss of life. The fewer details offered, the better. ("Racing Through the Night: Olympic's Attempt to Reach Titanic" Wade Sisson)

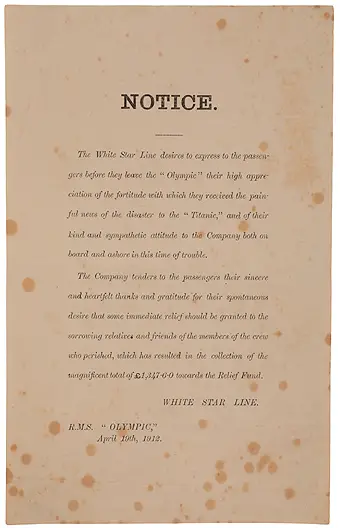

A notice put up on the 19th of April 1912, thanking

passengers. Credit: Duke's Auctions.

(Click image to enlarge)

When the Olympic resumed her voyage, Haddock had all concerts cancelled as a mark of respect. Once they had done all possible in transmitting wireless messages westward, Haddock allowed passengers to send and receive personal messages, although censoring them if necessary to ensure no further rumours were started.

Although having departed New York on the 13th of April it was not until the 21st - 8 days later - that the Olympic finally reached Southampton. It was a day late but understandable considering Haddock had made a 14 hour dash towards Titanic's reported position on the 15th and then spent most of the 16th stationary as they assisted with the wireless reports under Franklin's instruction. Additionally, Haddock had ensured they took a more southerly course to avoid the ice that had doomed her sister ship.

Just a day before arriving in England, on the 19th of April 1912, Haddock had a notice posted that thanked the passengers for their support and donations, that read:

The White Star Line Desires to express to the passen-

gers before they leave the "Olympic" their high apprec-

ciation of the fortitude with which they received the pain-

ful news of the disaster to the "Titanic", and of their

kind and sympathetic attitude to the Company both on

board and ashore in this time of trouble.

The Company tenders to the passengers for their sincere

and heartfelt thanks and gratitude for their spontaneous

desire that some immediate relief should be granted to the

sorrowing relatives and friends of the members of the crew

who perished, which has resulted in the collection of the

magnificent total of £1,347-6-0 towards the Relief Fund.

WHITE STAR LINE.

R.M.S. "OLYMPIC,"

April 19th, 1912.

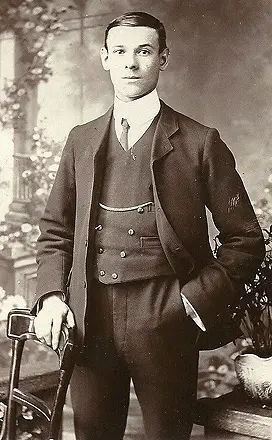

Captain Haddock's steward, Edwin Thomas Mills

Credit: Duke's Auctions. (Click to enlarge)

A copy of this solemn notice was kept as a souvenir by Captain Haddock's steward, Edwin Thomas Mills. Edwin was born in Hatfield Essex, and married Caroline Edith Mason on the 16th of April 1908 at The Holy Trinity Church, Hatfield Heath, and died in 1920. The notice was passed down by descent and then offered for auction by his granddaughter during Duke's Auctions' 11th of July 2024 auction in Dorchester where it fetched £2,700 (information courtesy of Duke's Auctioneers, Lot 142).

See also...

Next... Olympic Mutiny

If this website has been of some help, please consider supporting it with a coffee

to ensure it can continue. It can be anonymous. Anything helps!: