Captain Herbert Haddock

- Olympic Mutiny

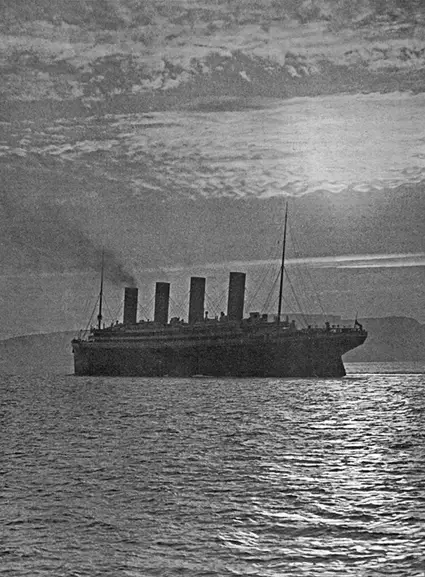

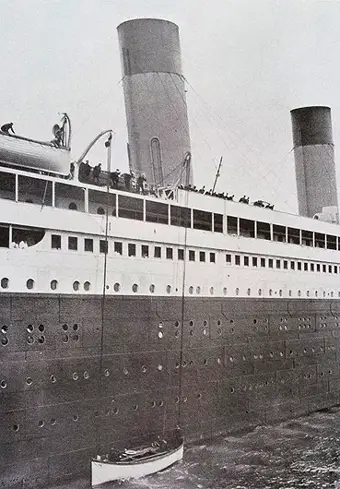

First known photo of RMS Olympic as she returned to port after the Titanic disaster, arriving at Plymouth, England on the morning of Saturday, April 20, 1912,

with her flags at half mast.

The Olympic's first port of call, with her flags flying half mast, was Plymouth harbour, at dawn on the 20th of April 1912, running a day late than normal. It was then that the passengers learned, via newspaper reports, of the full scope of the tragedy. The Olympic continued onto Cherbourg, arriving at 1.30pm which, in a strange coincidence, was an hour late just as the Titanic had been 10 days earlier.

When the Olympic finally arrived back in Southampton, in the early hours of Sunday the 21st of April, 1912, Haddock found the home port in a state of shock and mourning. But urgent work had to be done.

A black and white photographic lantern slide of the Olympic, with the following inscription: "'Flag at half mast' handwritten in white ink above the image. 'S.S. Olympic at/ Plymouth 20 Apl 12'. (LDPHT The Postal Museum, Calthorpe House, Object Number: 2010-0452/2)

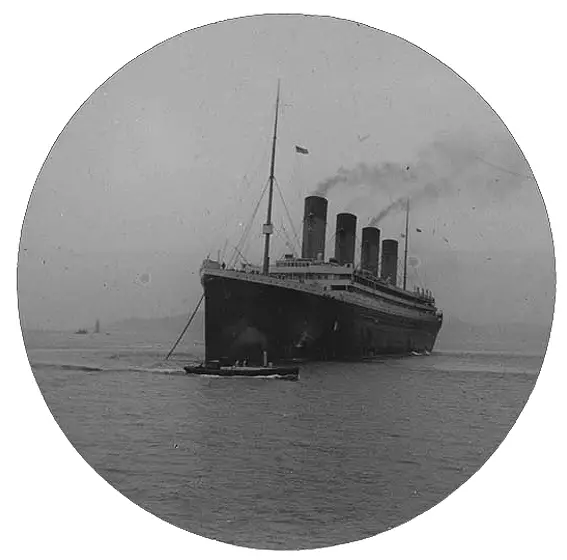

Haddock Criticism

Haddock was initially blamed for the incorrect report

of "All Titanic's passengers safe", such as in this

headline in the 15 April 1912 edition of The Evening Sun,

from Baltimore.

Returning to his home country, Haddock initially came under criticism from two reporters - Tewson and Leatherdale of The London Daily Express - who accused him of misleading initial reports with a message that read "All Titanic's passengers safe." Haddock, along with his two wireless operators, denied ever sending such a message. According to author Wade Sisson, Haddock drafted a statement that read: "In the presence of the Marconi operators, I have denied that such a message was received or sent from Capt. Haddock". ("Racing Through the Night: Olympic's Attempt to Reach Titanic," Wade Sisson)

A New York Times article of the 21st of April cleared up the origin of the rumour, stating that "Captain Haddock was able to-night to give to The New York Times the most dramatic possible explanation of the message attributed to him received on Monday in London and New York to the effect that all the Titanic's passengers had been saved and that the ship was being towed to Halifax" - with an explanatory headline: " Erroneous Report of Titanic's Safety Explained; How "Are All Titanic Passengers Safe?" and "Towing Oil Tank to Halifax" Became: "All Titanic Passengers Safe; Towing to Halifax." Haddock himself told reporters: "The story that I sent the report about the Virginian towing the Titanic is flagrant invention…The Olympic steamed nearly 400 miles before discovering that she would be too late to render any aid" ("Racing Through the Night: Olympic's Attempt to Reach Titanic," Wade Sisson)

Wireless Operators

Wireless operator Bagot wrote that when they arrived at Southampton they were "summoned to his cabin, Captain Haddock thanked us. For what?, we wondered." (Roaming Around by Alec Bagot). Haddock had earlier written a report to the Marconi Company dated 20 April 1912, commending the operators' work: "Can scarcely speak too highly of these officers' conduct at a very trying & anxious time. Mr Moore especially worthy of promotion. Thoughtful and reliable. (Signed) H.J Haddock."

Haddock himself arrived in Southampton exhausted - according to Sisson he was "so exhausted that he slept through the remainder of the morning." ("Racing Through the Night: Olympic's Attempt to Reach Titanic," Wade Sisson). Other newspapers also reported that when the Olympic returned to Southampton, Haddock looked exhausted and stressed. Perhaps he had an inkling of what was to come.

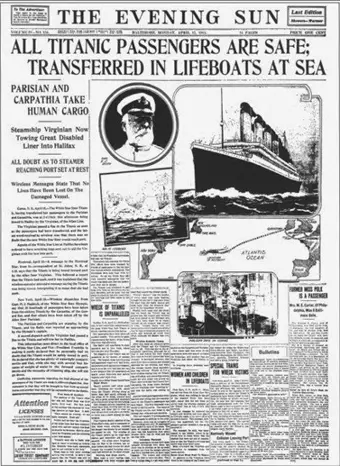

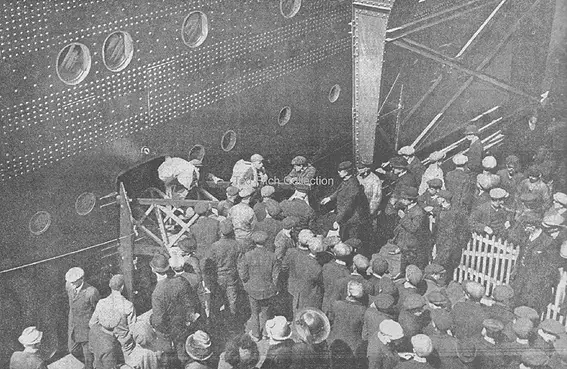

Extra lifeboats

The Olympic berthed at 44 while a number of Berthon

folding lifeboats are pictured being delivered.

(Click to enlarge)

Like Titanic, the Olympic did not carry enough lifeboats for everyone aboard, so the White Star Line hurriedly arranged for additional, second-hand collapsible lifeboats, reportedly taken from naval vessels moored nearby, to be added in preparation for her scheduled departure only three days later -the 24th April 1912.

But already there was a threat of mutiny rumbling. The New York Times ran an article on the 23rd of April, the day before sailing day with the headline: "RUSH TO MAKE OLYMPIC SAFE.; Otherwise, It Is Said, Passengers and Crew Will Refuse to Sail."

The following is a report of what happened and entitled "RMS Olympic – Mutiny over Titanic’s Boat Situation" by Terry Randall, dated 15th of April 1931:

Olympic arrived at Southampton in the early hours of Sunday 21st April to find their home port in a state of mourning, but despite the all-pervading gloom, activity in the dockyard was more intense than usual. At the White Star Dock, she had to be prepared for her next scheduled departure, due three days later on 24th April. In the light of recent events, considerable modifications were to be made to the life saving apparatus on the boat-decks before departure.

Collapsible boats on the Olympic's starboard boat deck

in April 1912. (Photograph: Southampton

Cultural Services) (Click image to enlarge)

Work immediately commenced to embark 40 Berthon collapsible lifeboats, to ensure there was sufficient lifeboat capacity for everyone on board. This was carried out under the watchful eye of the Board of Trade Assistant Marine Surveyor at Southampton, Captain Maurice Clarke; the man who had cleared Titanic for her sailing less than two weeks earlier. The embarking of the extra boats came under the direct supervision of White Star’s Marine Superintendent, Captain Benjamin Steele. Orders for the actual number of boats needed seemed to change hourly and at one point, after some 35 extra of these had been loaded, a message from the Liverpool office of White Star arrived stating that in fact only 24 extra boats were needed! As the surplus boats were landed ashore, rumours circulated that the reason for their landing was because Captain Clarke had failed to pass them as fit for use; two days later these rumours were to have a dramatic effect.

By breakfast time on Wednesday 24th April, the work had been completed, with the extra boats secured and covered. A number of temporary wire falls had also been installed and extra deck hands had been signed on to ensure that there were enough men to handle them. But despite the Herculean efforts of the Harland and Wolff workforce at Southampton, in the end their effort was for nothing.

("RMS Olympic – Mutiny over Titanic’s Boat Situation" by Terry Randall, dated 15th of April 1931)

While work continued on the ship, Haddock also granted an interview with The Daily Mail, under the headline of "The Olympic Messages" on the 22nd April 1912. It firstly allowed him an opportunity to express surprise that it was an iceberg that lead to Titanic's demise.

"A week before the Titanic sunk the Olympic passed over the very spot, or a few miles north of it, in broad daylight. We never saw a single particle of ice of any description, and from the bridge of the Olympic we could see, I should think, twenty miles on either side. " ("The Olympic Messages," The Daily Mail, 22nd April 1912)

The Daily Mail interview also gave Haddock further opportunity to clarify that he was not the source of the "All Saved from Titanic" message, stating it was a misunderstanding:

The message came from one of our old passengers, a lady in New York, and it was "Are all the Titanic passengers saved?" The lady had friends in the Titanic, and she was anxious about them. That message was received on Monday at about 10.20 or 10.27am." ("The Olympic Messages," The Daily Mail 22nd April 1912)

Captain Maurice Clarke from the Board of Trade inspects emergency boat no. 1 aboard Olympic in Southampton.(Source: Ioannis Georgiou/Encyclopedia Titanica)

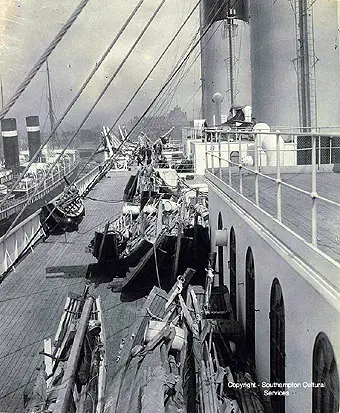

24th April 1912 Sailing Day Mutiny

The Olympic sits at berth 44 of the White Star Line dock

in Southampton in late April 1912 as one of the

folding Berthon lifeboats is tested following complaints

from crew. (Click to enlarge)

Despite the amount of work required, Haddock was ready to for a midday departure for New York, once Captain Clarke from the Board of Trade had cleared the ship for departure. There were 1400 passengers aboard, but within minutes of sailing Haddock had another challenge to face:

Making an early start, Captain Clarke went aboard at 0700 to inspect the new arrangements and give them an even more thorough examination than he gave the davits on Titanic two weeks earlier. As the passengers continued to arrive, he put the crew through their paces, having them uncover and lower a number of different boats to make sure that everything was in working order. The operation ran smoothly and Clarke estimated that it took an average of only twelve and a half minutes to lower each boat.

AT 1150 [am], satisfied everything was safe and on the verge of handing Captain Haddock his clearance to sail, a message was rushed to the bridge informing the captain that his stokehold crew was deserting the ship. A meeting was hastily arranged between the firemen and a number of company managers, but unconvinced by Captain Clarke’s assurances that the new boats were completely safe, the men refused to return on board unless the company replaced the collapsible boats with conventional lifeboats.( "RMS Olympic – Mutiny over Titanic’s Boat Situation" by Terry Randall, dated 15th of April 1931)

Olympic lifeboat 9 being tested by the Board of Trade

at Southampton at the time of the mutiny.

(Click image to enlarge)

Writer John Edwards also records that the Southampton White Star manager got involved:

On 24 April 1912, the day the strike began, P. E. Curry, White Star’s Southampton manager, warned Olympic’s crew that refusal to obey orders was “rank mutiny” and that “Capt. Haddock, if he pleased, could order the police to place every deserting fireman (back) aboard the ship.” Curry then promised that wooden lifeboats would replace all of the collapsible boats. According to a New York Times report, “The men were not satisfied and the entire staff of firemen, greasers, and trimmers, with but three exceptions, ceased work, collected their kits, and left the ship, singing, ‘We’re All Going the Same Way Home.'” (John Edwards, The Olympic Mutiny, https://oceanlinersmagazine.com/)

With no resolution, the voyage had to be postponed:

There was no alternative but to postpone the ship’s departure for New York until a replacement stokehold crew could be mustered. Olympic was then moved to a safe anchorage off Spithead in order to clear the berth, (also to make any further desertions impossible?) while 2nd Engineer Charles McKean remained onshore to muster this new crew. ( "RMS Olympic – Mutiny over Titanic’s Boat Situation" by Terry Randall, dated 15th of April 1931)

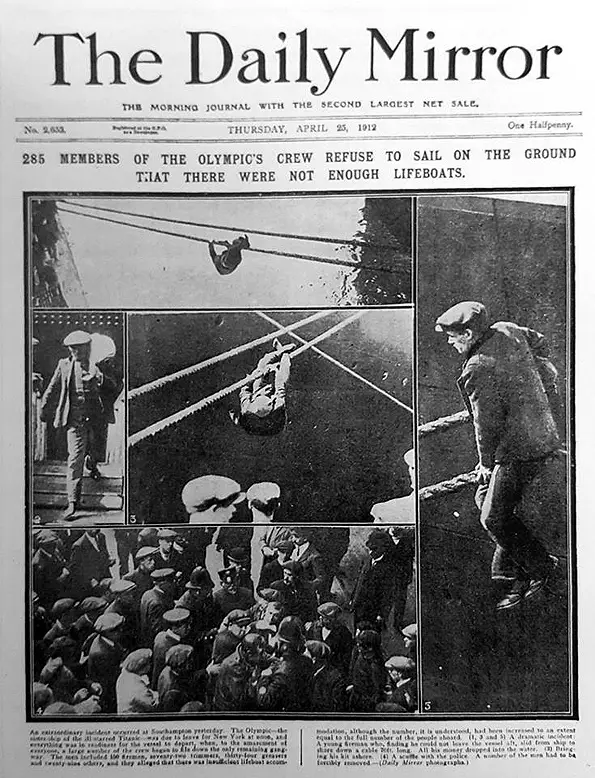

The Thursday April 25, 1912 edition of the The Daily Mirror shows "285 members of the Olympic's crew refuse to sail." (Click image to enlarge)

Replacement Crew

White Star needed to replace the strikers before the Olympic could continue on its voyage. But it proved a difficult task:

By dawn the next morning little had changed; Olympic remained anchored in the Solent with steam up and ready to sail. Not being one to waste time, Captain Clarke who had remained on board in order to be able to give Olympic immediate 'Clearance to Sail' the moment the new crew members arrived, he gathered a number of seaman on the boat decks to practice boat drill yet again. This time the results were not so reassuring, taking almost two hours to prepare and lower just a few boats. When some of the passengers began to appear on deck at around 0800, the exercise was stopped so that they would not be alarmed.

Later that morning the union delegation arrived to negotiate a settlement to the dispute and after discussions, six of the collapsible boats were lowered into the water and left for two hours. On examination it was found that five were totally dry inside, but the sixth did have a small amount of water in it. Closer examination revealed a tiny hole, but two hours of seepage could be easily bailed in less than three minutes. After a quick conference in the captain’s cabin, the union delegates agreed to advise their members that the boats were safe, provided the faulty boat was replaced.

As the afternoon wore on, with passengers on the decks in an increasingly impatient mood, the management and engineers ashore continued to sign on replacements, but it was not until 2200 that night that the tender finally arrived alongside with a total of 168 replacement stoke hold crew. This number included extra men considered adequate to allow Olympic to run at a faster speed than normal, in order to make up some of the 36 hours already lost. ( "RMS Olympic – Mutiny over Titanic’s Boat Situation" by Terry Randall, dated 15th of April 1931)

Due to sail on April 24, 1912, the Olympic's firemen went on strike. (Photograph: Tad Fitch collection) (Click image to enlarge)

More crew desert; passengers volunteer

White Star had been on the hunt for substitute firemen and trimmers and managed to recruit 100 men in Portsmouth and bring 150 more by special train from Liverpool and Sheffield. But it was not to be enough. The problem with the new crew was that they were non-union, causing another obstacle to the voyage:

At midnight, as Olympic was preparing once more to put to sea; another message arrived on the bridge telling Captain Haddock that more of his crew were deserting. Now another 53 men (35 A/B’s, 5 Quartermasters, 5 Look-outs, 2 Lamp-trimmers, 4 Greasers and two other engine room personnel) were boarding the tender that had brought out the new crew members; all refusing to sail with the ship.

This time the problem was not so much a lack of faith in the boats, but a lack of faith in the new crew! The seamen regarded the new stoke hold crew as either ‘the dregs of Portsmouth’,or inexperienced firemen not experienced in the running of a large ship; many of them did not even have “signing on" books.

Twice they refused Haddock’s orders to return to their duties, though they acknowledged their sympathies to him. A spokesman for the deserting seamen named Lewis admitted that the actions of the firemen at Southampton had been “a dirty low down trick", but their replacements were not fit to be aboard and that it would be unsafe to put to sea with them.

( "RMS Olympic – Mutiny over Titanic’s Boat Situation" by Terry Randall, dated 15th of April 1931)

It must have been a frustrating situation for Haddock and for the passengers - in fact 72 passengers volunteered to work in the stokehold, for which Haddock was thankful for the sentiment. One first class passenger, Ralph Sweet, who volunteered to be a stoker said:

"Our idea was that we should stoke the boat to Queenstown, where the Captain would have been able to get fresh men. About a hundred passengers vounteered altogether, and we would have been able to work in short watches. Capt. Haddock thanked us nicely, and I thought he was going to put us to work right away, but he told us afterward that he would not call on our services." ("Racing Through the Night: Olympic's Attempt to Reach Titanic," Wade Sisson)

George Granville Sutherland-Leveson-Gower,

5th Duke of Sutherland, between ca. 1910

and ca. 1915. He offered to help "stoke the boat"

(Bain News Service/Library of Congress)

The idea of volunteers came from the Duke of Sutherland, also a passenger on board, who had arranged a meeting in the Olympic's First class smoking room to propose a solution. In addition to working in shifts, the Duke also offered to raise a crew of yachtsmen. Some saw it as a criticism of Haddock's leadership, but the Duke ultimately ended up praising Captain Haddock's handing of the situation:

"I think all the passengers will be sorry that they are not sailing under Captain Haddock's care. As for the complaint that he did not give the passengers sufficient information, I do not know what more he could have given them. Certainly he told them everything he knew. He got the firemen, and I have no doubt that if he had had more time he would have got the rest of the crew together." ("Racing Through the Night: Olympic's Attempt to Reach Titanic," Wade Sisson)

Navy help: HMS Cochrane

The second wave of mutineers was the final straw for Haddock. He had to take action. Curiously, the Olympic lay anchor just off Spithead, which was the scene of a successful Royal Navy mutiny in 1797, known as "The Spithead and Nore mutinies." It was appropriate then that Haddock called on the Royal Navy for assistance.

According to The New York Times of 27 April 1912, "the seamen then began to climb from the Olympic into the tug which had brought the strikebreakers. Capt. Haddock of the Olympic ordered them to return, but without effect. He then signaled by lamp to the cruiser Cochrane, whose Captain came aboard and warned the men that they were guilty of mutinous behavior and liable to heavy punishment. The men refused to return."

The Times dated 27th April 1912 gave further details regarding Haddock: "Standing on the edge of a doorway in the side of the Olympic, the captain solemnly warned these offenders against the course they were pursuing, and ordered them to return to the ship. But his exhortations proving of no avail, signals were sent, first by wireless, and when no attention was attracted, then by Morse flash lights, to the Cochrane, which was the nearest warship, intimating that part of the crew had deserted, and asking for assistance."

Haddock called on the assistance of the HMS Cochrane at just before midnight:

Admiral Sir William E. Goodenough, 1919.

(Photograph: © National Portrait Gallery, London.)

Shortly after midnight, Haddock signalled the commander of the Royal Naval cruiser HMS Cochrane lying half a mile away off Spithead:

“Crew deserting ship; request your assistance. Haddock, Master.”

Within half an hour Captain W E Goodenough RN had boarded Olympic to help mediate in the dispute and try to persuade the men to return to their duties.

Although a number of the men were still dissatisfied with the boats, the majority were more concerned at the lack of experience in the new men; many of them were not even union members. It was this last point that Captain Goodenough considered to be the root cause of the new situation, believing that the men seemed to be more afraid of their union than any possible repercussions from their actions. The threat of a charge of mutiny failed to influence the men and the use of force could not be considered as nobody had been hurt or threatened; in fact the men had shown every respect for the two officers. ("RMS Olympic – Mutiny over Titanic’s Boat Situation" by Terry Randall, dated 15th of April 1931)

HMS Cochrane

(Imperial War Museums/collection no. 2107-01)

April 26th: Voyage Cancelled

Despite last minute efforts to acquire more crew, Haddock realised he was caught in a proverbial catch 22 situation and the only solution now seemed to cancel the voyage.

With a new stalemate on board, the White Star management at Southampton wearily set about raising a new deck crew in the early hours of the morning and at 1100 the tender again arrived alongside with over thirty new men; though Captain Clarke failed to pass but a few as fit for duty. A little over an hour later, Clarke received word from his office to clear Olympic for departure as soon as he was satisfied the ship was sufficiently manned, but with the ship already two days behind schedule, this seemed less likely than ever.

At 1500, the expected news to cancel the voyage arrived from the White Star Liverpool offices and Olympic returned to Southampton to disembark her passengers. She would remain there until her next scheduled voyage with union approved boats (and crew) on the 15th May. ( "RMS Olympic – Mutiny over Titanic’s Boat Situation" by Terry Randall, dated 15th of April 1931)

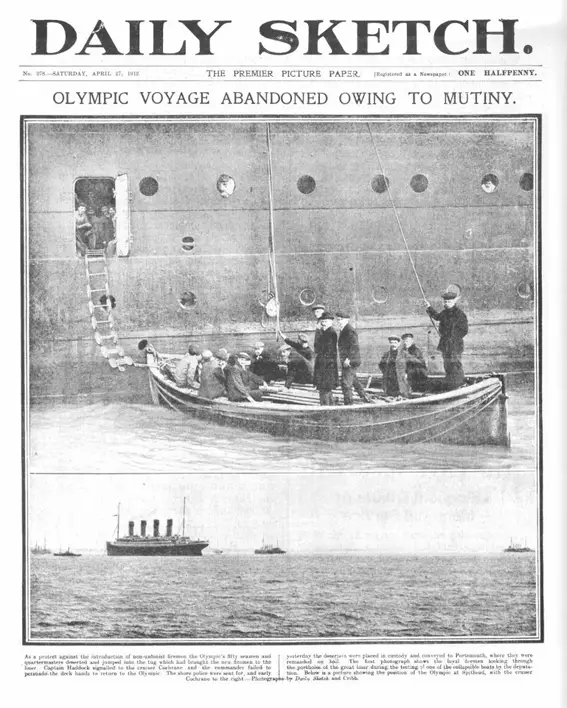

The Saturday April 27, 1912 edition of the Daily Sketch shows two photographs from the mutiny: "Loyal fireman looking through the portholes of the great liner during the testing of one of the collapsible boats by the deputation. Below is a picture showing the position of the Olympic at Spithead". (Click image to enlarge)

The White Star Line, who had to refund all the passengers money now that the voyage was cancelled, were not happy with this further blow to the company. In a telegraph to the Postmaster General explaining the delay to the mail (the Olympic was a Royal Mail ship like Titanic after all) they wrote:

Earnestly hope you will secure for us… the proper punishment of crew's mutinous behaviour, as unless firmess is shown now we despair of restoring discipline and maintain sailings. (And the Band Played On, Christopher Ward)

The Olympic would not sail until the 15th of the following month, during which time the ship was visited by Lord Mersey while she was idle in Southampton, for the upcoming British Board of Trade Inquiry into the disaster.

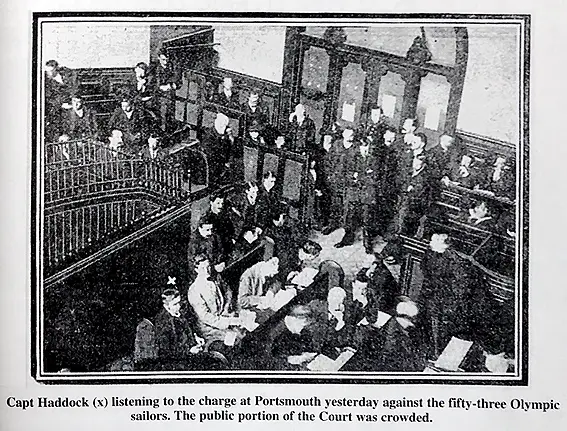

Court Case

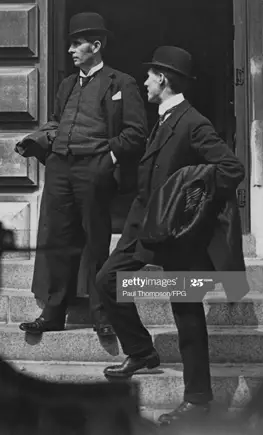

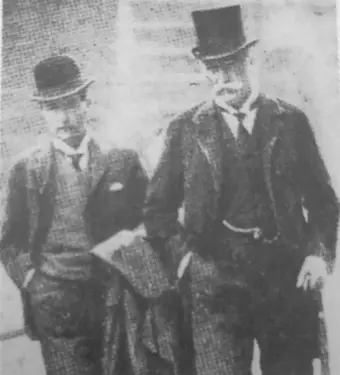

Herbert Haddock (left) pictured in

Portsmouth in 1912 (Photograph: Getty

Images) (Click to enlarge)

One key issue with the court case that the White Star brought against the mutinous men was the quality of the replacements. An exNaval officer and quartermaster, George Martell was one of the witnesses for the defence who stated that he was "throughly disgusted by the appearance of the men whipped into take the place of the striking firemen... They were the scallywags of Portsmouth." (And the Band Played On Christopher Ward). But ultimately White Star would have the charges of mutiny proven:

The mutiny was over, but for the White Star Line, the entire incident following hard on the loss of Titanic had added insult to injury. If the company was ever to recover any of its lost credibility, then action had to be taken; this action took the form of a court case against the 53 seamen who had deserted the ship after sailing from Southampton.

The case began on Tuesday 30th April in the Portsmouth Police Court when the accused men answered to the charge that:

“…..they were guilty of wilfull disobedience to the lawful commands of Captain Haddock, Master of the steamship Olympic, contrary to section 225 of the Merchant Shipping Act, 1894.”

The defence lawyers based their case on Article 458 of the same act claiming that as owners, the White Star Line was obliged to ensure the seaworthiness of their ships, but in allowing Olympic to sail with an incompetent crew ("the scallywags of Portsmouth’), it almost amounted to rendering her as not seaworthy; as if she had a hole in her hull!

Norman Raebarn, acting for the White Star Line, called Captain Benjamin Steele, the White Star Marine Superintendent at Southampton, to testify that the life-saving equipment on board was adequate and Captain Clarke was subpoenaed by the company to testify that all the boats were seaworthy and had an adequate number of seamen to handle them.

Regarding the competence of the replacements, Second Engineer Charles McKean, who had mustered the new stoke hold crew, admitted that many of the new men were inexperienced (many were Yorkshire miners), but he did not consider the job of fireman to be skilled labour, though he did admit much to the amusement of the court, that it was hard work.

The verdict announced on 5th May went in favour of the White Star Line, but in summing up, the judge decided that it would be inappropriate to fine or imprison the mutineers as they had probably been unnerved by the recent Titanic disaster; it was probably as good a result as the White Star Line was going to get. With attention now centred on Lord Mersey’s enquiry in London into the loss of Titanic, the incident was relegated to the background, as the company’s lawyers faced the more daunting task of salvaging their employer’s reputation in a more public arena. ( "RMS Olympic – Mutiny over Titanic’s Boat Situation" by Terry Randall, dated 15th of April 1931)

Herbert Haddock photographed inside the court, marked with an X. (Daily Sketch, 1 May 1912) (Click image to enlarge)

Results

On May the 15th, the mutinous men finally returned to the Olympic, greeted by the sight of new Harland & Wolff wooden lifeboats installed on the boat deck.

The one man who perhaps gained from the mutiny was Captain Clarke. As Board of Trade Surveyor he was not paid for any overtime, but his sixty hours marooned on Olympic had been above and beyond the call of duty. He was given a bonus payment of £6-16-0 (£6-80p) to compensate him for the extra work, which did a great deal to make up for the three-day backlog that had built up on his desk while he had been away. The extra cost was passed on to White Star in the form of an excess charge of £16.

The episode was over, but not quite forgotten. On the 14th May a question was tabled in Parliament by George Terrell MP to Prime Minister H H Asquith enquiring "what action if any, was to be taken against the officials of the British Seafarers Union, who had prevented the departure of Olympic, consequently delaying His Majesty’s Mails’. Terrell’s question was referred to the Board of Trade, who unsurprisingly decided, that as a result of the court case at Portsmouth, no prosecution was worthwhile!

Olympic meanwhile remained at Southampton until midday 15th May, when she sailed, without event, on the start of her sixth voyage to New York and back. ("RMS Olympic – Mutiny over Titanic’s Boat Situation" by Terry Randall dated 15th of April 1931, http://coss.org.uk )

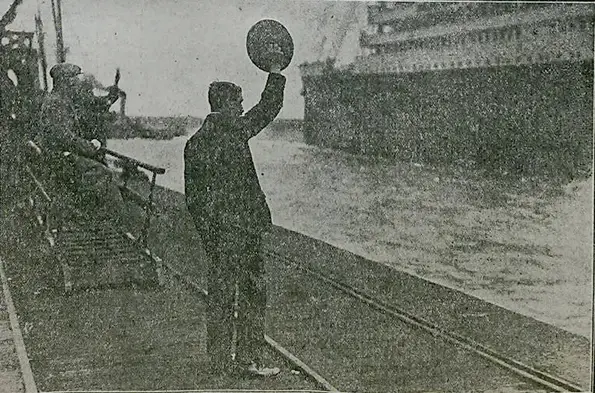

A newspaper photograph of Titanic survivor 2nd class boots steward Joseph Chapman pictured waving off the Olympic. The newspaper caption reads: "After an enforced delay of three weeks the Olympic left Southampton for New York on Wednesday"

Titanic Inquiries

But all was not over for Captain Haddock. Having finally departed Southampton on the 15th of May 1912, precisely a month after the fateful day Titanic sank, with slightly more than 400 passengers aboard (1000 less than during the munity, and the lowest of her career) the Olympic arrived in New York on the 22nd of May. She was scheduled to depart on the 25th of May for the return trip to Southampton. But before leaving on the 25th, Senator William Alden Smith, who was presiding over the Senate Inquiry in to the Titanic disaster, came aboard and questioned Captain Haddock and wireless operator E.J. Moore. Wyn Wade in his book "Titanic - End Of A Dream" notes that the visit came as a complete surprise to Haddock, who immediately called up P. A. S. Franklin at the IMM who told Haddock to give Senator Smith whatever he needed.

Herbert Haddock (left) in an undated photograph aboard the Olympic's boat deck, with who appears to be Senator Smith - perhaps on the occasion of his tour during the Senate's Titanic inquiry (25 May 1912).

(Courtesy of Louis Francken)

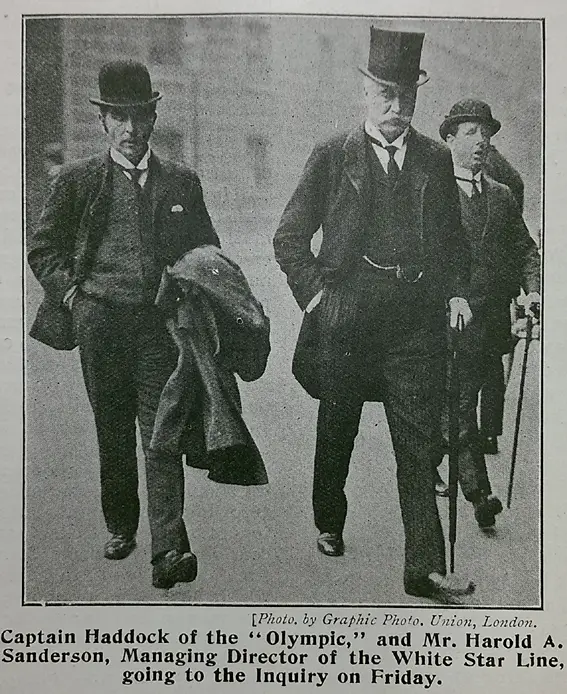

Herbert Haddock (left) and Harold Sanderson

photographed at the British Inquiry (Triumph and Tragedy).

According to the Senate record kept of his interview, Haddock stated his "business" as a "Master Mariner" and that he first heard of Titanic's collision from "Mr Moore, the wireless operator" when "roughly, we were west by south 500 miles of the Titanic" at "New York time, 10.50 p. m., Sunday." Smith went on to question the various wireless messages, in particular examining whether the Olympic had withheld information or been involved in starting the initial rumours about the disaster.

Moore gave Smith a copy of the ship’s wireless log and Haddock took the senator and his group on a tour, which included a lifeboat, which was lowered fully loaded with sailors. Haddock even introduced Smith to fireman Frederick Barrett from the Titanic:

"Haddock mentioned that Frederick Barrett, leading fireman on Titanic, was on board. He then led Smith to the boiler room, where Barrett described for the senator and his party what had happened on board Titanic in the aftermath of the collision with the iceberg." ("Racing Through the Night: Olympics' Attempt to Reach Titanic" - Wade Sisson)

Satisfied with answers from Haddock and Moore, the witnesses were then excused and Haddock allowed to command the Olympic on her return voyage to Southampton.

Herbert Haddock in a Daily Graphic newspaper clipping. (Courtesy of Paul Lee)

Herbert Haddock photographed outside the British Inquiry, holding a coat.

(Click image to enlarge)

Sometime between May and July 1912, Haddock also attended the British Inquiry, although unlike in the United States he was not asked to testify. He is photographed walking swiftly outside the Inquiry. At the time he and his family were living at 40, The Avenue, Southampton (now the site of the Travelodge). Also during May 1912, Herbert and Mabel's oldest son, 17 year old Geoffrey Haddock, emigrated to Canada as a passenger on the SS Canada, which left Liverpool on 18th May 1912, and arrived in Quebec on 26th May 1912. It had departed England only a few days after his father's much delayed voyage to New York. (Jackie Chandler/Southampton Cenotaph)

See also...

Next... Olympic Refit

If this website has been of some help, please consider supporting it with a coffee

to ensure it can continue. It can be anonymous. Anything helps!: