Side Menu:

Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall

- Sinking & Carpathia

Boxhall in charge of lifeboat no.2 was "about a half a mile away... resting on the oars" when the Titanic sank. (US Inquiry). But he did not see her final moments:

"I cannot say that I saw her sink. I saw the lights go out, and I looked two or three minutes afterward and it was 25 minutes past 2. So I took it that when she sank would be about 20 minutes after 2… I would say we were then about three-fourths of a mile from her." (US Inquiry)

At that distance they were not close enough to experience any suction that he had earlier: "I do not think there was the suction that the people really thought there was. I was really surprised, myself…By hearsay, it seems to have been a general surprise to everybody that there was so little suction. (US Inquiry)

The sea was perfectly smooth when we left the ship. Every star in the heavens was visible, but there was no moon. So it was dark. And then, well everything was very peaceful … no wind … and no moon, stars, smooth water, until after about an hour then the wind got up and there was a little sea. For a long time we didn't move the boat, when we laid off on the Starboard side. You could see by the arrangements of the lights, all the lights were burning and you could see that she was going down. You could see that her stern was, was getting pretty low in the water. She was certainly going down, there was no doubt about it then. And, well we pulled, we got away clear of the ship and we just laid on the oars until eventually they realized that she'd gone and we heard all the screams. (BBC interview October 1962)

Although Boxhall could not see what happened he did hear it: "I heard cries. I did not know when the lights went out that the ship had sunk. I saw the lights go out, but I did not know whether she had sunk or not, and then I heard the cries. I was showing green lights in the boat then, to try and get the other boats together, trying to keep us all together." (British Inquiry)

When asked if he went back towards the ship when he heard those cries, Boxhall replied; "No, I did not... There was a suggestion made. I spoke about going back to the sailor-man that was in the boat - that was whilst I was pulling round the stern - about going back to the ship, and then I decided that it was very unwise to have attempted it. So we pulled away, and then we did not pull back at all. (British Inquiry)

A close up on lifeboat no.2 in Ken Marschall's illustration.

Boxhall did not see anyone in the water "I could not see anybody in the water. I was looking around for them, keeping my eyes open, but I did not see anyone." If he had seen somebody he would have "taken them in the boat at once... I should have taken them in as far as safety would allow; but I did not see anyone in the water." (US Inquiry)

Later he said there was nothing they could do: "We couldn't do anything. And the screams went on for some considerable time. I can't remember the time when she sank, but it was in the early hours." (BBC radio interview October 1962)

They could not see anything at all and after the cries disappeared they could hear the sound of nearby icebergs:

"I saw nothing; but I heard the water on the ice as soon as the lights went out on the ship… A little while after the ship's lights went out and the cries subsided, then I found out that we were near the ice... I heard the water rumbling or breaking on the ice. Then I knew that there was a lot of ice about; but I could not see it from the boat… Of course, sound travels quite a long way on the water, and being so close to the water, and it being such a calm night, you would hear the water lapping on those bergs for quite a long, long ways.. It was like an oily calm when the Titanic struck, and for a long, long time after we were in the boats, and you could not see anything at all then." (US Inquiry)

The noise of the water against the icebergs was also likely caused by a light wind that came up: "I didn't see any ice whilst I was in the boat, but I could hear, there was a little breeze sprang up before we got to the Carpathia, and I could hear the water on the ice, field ice or whatever it was, but I never saw any ice until after we'd been picked up by the Carpathia." (1962, BBC)

Lifeboat Lights

Although he didn't see any of the icebergs at this point, he did see some of the lamps from other lifeboats: "I saw several of the boats - in fact all of the lifeboats - when I was in my boat, which had lighted lamps in them…before I saw the Carpathia… I could see the reflection of the lights; I did not see the lights themselves…not that they all had lights burning, but I saw several. " (US Inquiry)

Boxhall described the usual lifeboat lamps as "very dim, small lamps" however the green lights in lifeboat no.2 were green.: "I had been showing green lights most of the time. I had been showing pyrotechnic lights on the boat." (US Inquiry)

The original intention of the green lights was the bring the lifeboats together: "I did not see any boat near us, although I was showing these green lights occasionally, with the intention of getting all the boats together. There was not a boat anywhere near us. I did not see any. (British Inquiry)

These green lights drew the attention of the rescue ship, with the Carpathia "steaming toward our green lights" (US Inquiry). In fact lifeboat no.2 was the first to be spotted by the Carpathia no doubt due to her distinctive green lights which meant it "was the first boat picked up on board the Carpathia... he saw our green lights and steamed down for them." (British Inquiry)

Mrs Douglas reported in her affidavit to the Senate: "Mr. Boxhall had charge of the signal lights on the Titanic, had put in the emergency boat a tin of green lights, like rockets. These he commenced to send off at intervals, and very quickly we saw the lights of the Carpathia, the captain of which stated he saw our green lights 10 miles away, and, of course, steered directly to us, so we were the first boat to arrive at the Carpathia." (US Inquiry)

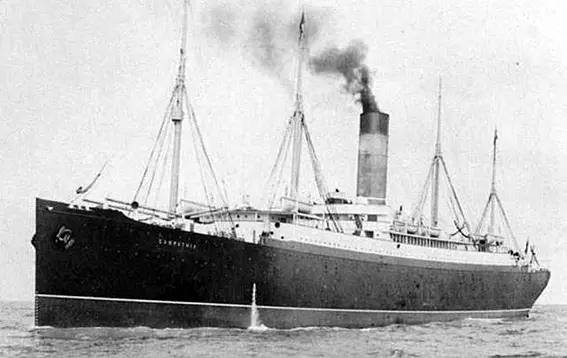

The Cunard liner RMS Carpathia at sea.

The first thing Boxhall saw of the Carpathia was her rockets: "Eventually we saw a rocket go up and it turned out to be the Carpathia, so she'd seen my green light that I'd burnt, so I burnt another one. And eventually she steered for the position that I was in, and consequently I was the first boat picked up." (1962, BBC)

Boxhall thinks he saw the Carpathia's rocket three-quarters of an hour before they were rescued and described it as "an ordinary rocket. I think it was, so far as I could see, a distress rocket in answer to ours." (US Inquiry) and as the sun rose, Boxhall also noted icebergs: " I got within about two or three ship's lengths of the Carpathia, when I saw her engines were stopped - then I saw the icebergs; it was just breaking daylight then.. He seemed to have stopped within half a mile or quarter of a mile of the berg… Numerous bergs. As daylight broke I saw them…And field ice. I could see field ice then as far as the eye could see." (US Inquiry) Later he added: "The first ice I saw, I saw it probably about half a mile on the port bow of the “Carpathia” just as I was approaching it, when I got about two ships’ lengths away from her. Day was breaking then." (British Inquiry)

Second officer James Bisset of the Carpathia remembers sighting Boxhall's lifeboat. In his book, "Tramps and Ladies" (1959), Bisset remembers:

"First Officer Dean was relieved on the bridge by Chief Officer Hankinson. At that moment, in the dim gray light of dawn, we

sighted a lifeboat a quarter of a mile away. She was rising and falling in the ocean swell, and now, as so often happens at dawn, a

breeze sprang up and whipped the surface of the water to choppy seas.

The boat was laboring toward us. In her sterns stood a man wearing officer's cap and uniform, steering with the tiller. Only

four other men were in the boat, each of them with an oar, but rowing feebly, as though they were inexperienced, and also utterly exhausted. Huddled in the boat were twenty-five women and ten children." ("Tramps and Ladies" by Sir James Bisset, P.R.Stephensen, 1959)

4am: Carpathia

Mrs Douglas, still handling the tiller, described the moment they pulled alongside the Carpathia and began to panic - to which Boxhall told her to "shut up":

"When we pulled alongside Mr. Boxhall called out, "shut down your engines and take us aboard. I have only one sailor." At this point I called out, "The Titanic has gone down with everyone on board”, and Mr. Boxhall told me to "shut up." This is not told in criticism; I think he was perfectly right. We climbed a rope ladder to the upper deck of the Carpathia. I at once asked the chief steward, who met us, to take the news to the captain. He said the officer was already with him." (US Inquiry, affidavit)

As if it ensure that meant no criticism of Boxhall, Mrs Douglas added: "Mr. Lightoller and Mr. Boxhall were extremely courteous and kind on board the Carpathia. I think them both capable seamen and gentlemen." (US Inquiry, affidavit). Boxhall described the boarding of the Carpathia: " I handed everybody out before I came out… There was a stepladder up the side… a direct ladder.… put the rope over their heads; put their arms through a rope, and then assisted them up in that way… They told me on board the Carpathia afterwards that it was about 10 minutes after 4, approximately. " (US Inquiry)

In 1962 the time of boarding Carpathia changed to five minutes to four: "People on the Carpathia told me it was about, just before four o'clock, about five minutes to four, I think. And I got alongside there and everything was ready, derricks was hoisted, derrick falls with bowlines in them, and there was ladders over the side, absolutely everything had been done that was possible to be done. (1962 BBC radio broadcast)

Second officer James Bisset (here pictured in

1906) of the Carpathia wrote about picking up

Boxhall and boat no.2. (Click to enlarge)

Second officer Bisset of the Carpathia also remembers the difficulty of rescuing this first lifeboat they had sighted:

With the breeze that had sprung up, the boat was on our windward side, and drifting toward us. It was not practicable to maneuver the Carpathia to windward of the boat, so that she could make fast on our lee side in the smoother water there, as correct seamanship required. A large iceberg was ahead of us, which would have made that maneuver difficult when time was the chief consideration. If the boat had been well manned, she could have passed under our stern to the leeward side; but, as she drifted down toward us, the officer sang out, "I can't handle her very well. We have women and children and only one seaman."

Captain Rostron gave me an order, "Go overside with two quartermasters, and board her as she comes alongside. Fend her off so that she doesn't bump, and be careful that she doesn't capsize."

I hurried with two seamen to the rail of the fore deck, where rope ladders were hung overside. As the boat came alongside,

we climbed quickly down and sprang onto her thwarts, and, by dint of much balancing and fending off, succeeded in steadying the boat and dropping her astern to an open side door on "C" Deck, where we made her fast with her painter to lines lowered by willing hands from the doorway. Many of the women and children castaways were seasick from the sudden choppy motion of the boat caused by the dawn breeze. All were numbed with cold, as most of them were lightly clad. Some were quietly weeping.

As they were in no fit condition to climb safely up the short Jacob's ladder to the side door, bosun's chairs were lowered, also

canvas bags into which we placed the children, and, one at a time, they were all hauled to safety. During this operation, we were occupied with allaying the fears of the women and children, and getting them safely out of the boat. They behaved well, waiting their turns to be hauled up to the door. As we fastened one of the women into a bosun's chair, I noticed that she was wearing a nightdress and slippers, with a fur coat. Beneath the coat she was nursing what I supposed was a baby, but it was a small pet dog! "Be careful of my doggie," she pleaded, more worried about her pet's safety than her own." ("Tramps and Ladies" by Sir James Bisset, P.R.Stephensen, 1959)

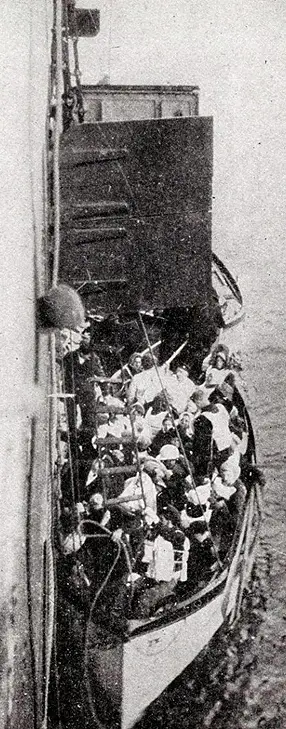

Lifeboat no.11 with passengers using a ladder

to get onboard the Carpathia.

(Click image to enlarge)

Boxhall remembers waiting to be the last off the lifeboat and his conversation with Captain Rostron:

And the Captain kept sending down to know if there was an officer in the boat, and to send him up at once, but I sent the message back, “When I get the boat empty, then I'll come up. And I've only got one sailor in the boat.” And, eventually the boat emptied and then I went up to the Captain, Captain Rostron, on the bridge. And he said, “Where is the ship?” I said, “she's sunk.” And I said, “I don't know where the other boats are, I've not seen them, they're all to the southward of us somewhere.”(1962 BBC Broadcast)

Second officer Bisset also remembers seeing Boxhall for the first time and his anguished conversation with Captain Rostron:

When the women and children had been sent up, the four oarsmen and the officer climbed up the ladder the officer being the last of the castaways to leave the boat. I followed him up, leaving our two seamen in charge of the boat, to hook her on to Number One derrick, ready to be hoisted to our foredeck. The officer was a young man, Joseph Boxhall, Fourth Officer of

the Titanic. I took him up to the bridge, to report to our Captain.

Without preliminaries, Rostron burst out, excitedly, "Where is the Titanic?"

"Gone!" said Boxhall. "She sank at 2.20 A.M."

In the moment of stunned silence that followed, every man on the bridge of the Carpathia could envisage the appalling reality, but not yet to its fullest extent. It was now 4.20 A.M.

Boxhall added, in a voice of desperation, "She was hoodoo'd from the beginning. . . ."

Captain Rostron took the young officer by the arm, and said quietly and kindly to him, "Never mind that, m'son. Tell me, were all her boats got away safely?"

"I believe so, sir. It was hard to see in the darkness. There were sixteen boats and four collapsibles. Women and children were

ordered into the boats. She struck the berg at 11.40. The boats were launched from 12.45 onwards. My boat was cleared away

at 1.45, one of the last to be lowered. Many of the boats were only half full. People wouldn't go into them. They didn't believe that she would sink . ."

"Were many people left on board when she sank?"

"Hundreds and hundreds! Perhaps a thousand! Perhaps more!" Boxhall's voice broke with emotion. "My God, sir, they've gone down with her. They couldn't live in this icy cold water. We had room for a dozen more people in my boat, but it was dark after the ship took the plunge. We didn't pick up any swimmers. I fired flares ... I think that the people were drawn down deep by the suction. The other boats are somewhere near. . . ."

"Thank you, Mister," said Rostron. "Go below and get some coffee, and try to get warm." ("Tramps and Ladies" by Sir James Bisset, P.R.Stephensen, 1959)

As it happened Boxhall was "on the bridge for a few minutes, shortly after we got the boats on board…About a quarter of an hour," and remained there as they "were steaming around the wreckage for quite a long time. I did not notice the time, but it must have been quite late in the forenoon." (US Inquiry)

Although Boxhall helped with the rescue of other lifeboats: "I was down in the other boats. I suppose a good half an hour had elapsed before any of the other boats were there." (British Inquiry)

The first boat did not arrive until at least half an hour after I arrived there… and then I had passed up crews from either two or three boats from the same gangway before Mr. Ismay came… he came alongside in the collapsible boat outside of the Carpathia. ..I do not know any number; it was a collapsible boat. ..It was one of the last boats that came…I did not take that much notice. One did not stop to look what men were there in the boats or who they were; it was just a case of passing them out. " (US Inquiry)

Lightoller (middle) talks with Captain Arthur Rostron (right) on board R.M.S. Carpathia looked on by the ship's Chief Officer Hankinson

"And it was daylight eventually before any boats where sighted, and it was nearly eight o'clock, I think, as near as I can remember, it was certainly broad daylight when we picked up the other boats. We cruised around in the Carpathia then, and eventually picked up all the other boats. And some of them were hoisted and left in their davits and some of them were turned in and put in on the deck." (BBC interview October 1962)

When the Carpathia was steaming around the scene of the wreck, Boxhall also saw icebergs "there were numerous icebergs; that is the easiest way or the best way to express it. " (US Inquiry) and he also saw a body in the water: " I saw one floating body…A man… It had a life preserver on…quite dead…We could see by the way the body was lying. … This body looked as if the man was lying as if he had fallen asleep with his face over his arm... That is the only body I saw" (US Inquiry).

In a letter written in 1962 Boxhall also wrote about seeing a body: "Captain Rostron steamed over the ground searching for survivors but all we saw was one body of a man floating on his back in a dinner jacket. There was some flotsam-fittings, deck chairs and a considerable amount of granulated cork used by ship's painters under the deck heads whilst the paint is wet. It was some time later-(usually 10 days) when the bodies came to the surface, when the cable ship Mackay Bennett from Halifax recovered a very great number and took them to Halifax N.S." (letter written 22 July 1962, courtesy of Joe Carvalho & Shelley Dziedzic, Encyclopedia Titanica)

After all the lifeboats had been rescued Boxhall "remained on the bridge until he started off for New York direct. I do not know what time that was." (US Inquiry)

"We steamed over the ground in the daylight. The California, Californian, she appeared. I don't know, I don't remember seeing any other ships. The captain was going to put his officers on watch and watch, so we Titanic Officers, the juniors, that was Moody[sic], and Moody[sic] and Pitman and I, we, ah, we went on watches, we took soundings, and of course we got fog all the way into New York." (BBC interview October 1962)

Boxhall was later given an autographed photograph of the Carpathia officers as a gift.

Autographed photograph of Carpathia's officers given to Fourth Officer Boxhall. Credit: Titanic Voices/Ford Collection. (Click image to enlarge)

If this website has been of some help, please consider supporting it with a coffee

to ensure it can continue. It can be anonymous. Anything helps!: